Good or Evil? How AI Is Transforming Life, Work and Society

Will artificial intelligence turn out to be a blessing or a curse? DLD speakers from science, business and technology share expert opinions.

First they outsmarted chess masters, now they’re learning how to become doctors, copywriters, composers, lawyers and even software developers: powered by artificial intelligence, computers manage to perform ever more tasks on a human level.

The rapid progress in AI makes many people wonder: where is all of this going?

“What I’m curious about is: Is this a Black Mirror episode? Or is this an episode of Star Trek?”, Laura Summers, founder of Debias AI, mused at DLD Munich in January. “Are we living in a dark world, a light world or something in the middle?”

Most likely, it will be a mix of the above, as a number of DLD23 sessions about the new capabilities of generative AI systems, such as ChatGPT, showed. Trained on billions of texts, images and videos culled from the Internet, these algorithms are able to generate content that’s often hard to identify as the creation of an AI.

But does that mean that supercomputers, tapping into all the Web’s knowledge, will soon acquire superhuman intelligence as well?

Robotic Parrots

As impressive as ChatGPT, DALL-E and smimilar systems are, it’s important to keep in mind that they have no concept of what they are dealing with. They have been programmed to produce answers based on rich training data and enormous amounts of computing power – and ultimately, much of the process comes down to statistics.

“What’s happening here is really dramatic. It’s like, ‘Oh, my God, I didn’t really think we could do these things!’”, former MIT researcher John Clippinger admits, before adding: “The technology in some sense is trivial, though. It is sort of like a robotic parrot.”

Tech veteran Phil Libin also cautions against reading too much into the current excitement over generative AI systems “They’re very impressive but they’re not reasoning”, Libin says. “They have no connection to facts and rules and symbolic logic.”

Challenges of Generative AI // Michele Ruiz (BiasSync), John Clippinger (Bioform Labs), JP Rangaswami (Web Science Trust), Björn Ommer, Ludwig Maximilian University, Richard Socher (You.com), John Thornhill (Financial Times)

JP Rangaswami, Chairman of the Web Science Trust, is impressed by the technology: “It’s performing tasks that we used to associate with human intelligence far better than we would have anticipated”, he says. “I think there is an incredible potential for what we see.”

But the public debate, he feels, is focusing too much on the near-term impact of AI.

“The hype”, Rangaswami adds, “makes me think of Amara’s law: that we are grossly overestimating the impact of this in the short run, and possibly grossly underestimating the impact of this in the long run.”

How quickly will AI keep getting smarter, and to what effect? This is perhaps the most passionately debated issue in computer science at the moment, prompting many researchers and tech executives to sign an open letter demanding to “Pause Giant AI Experiments” for at least six months.

The State of Truth and Trust at Work // Phil Libin (All Turtles) and Ina Fried (Axios) explore technology in the office world

The Disinformation Machine

One of the biggest worries many experts share is that cutting-edge AI systems are able to produce texts, images and even videos based on simple prompts by human users. This has already given us seemingly real, but entirely invented pictures of the pope in a puffer jacket and Donald Trump getting arrested by the police.

These early experiments with mass-produced deepfakes quickly got debunked – but what about others?

“We’re going to get an arms race of people with nefarious purposes, trying to use generative AI to influence our decision making”, warns Mehran Sahami, a leading computer scientist at Stanford University.

In response, people have to get skilled at identifying and verifying information, Sahami argues.

“We have millions of years of evolution that have made our eyes and ears our primary inputs for information about the world”, he says. “And we can no longer trust those things unless we experience it ourselves. And that’s a profound shift for our species.”

Worried by such prospects, the European Parliament has adopted the draft of a new AI Act. If passed, the law would be the first anywhere in the world to regulate how artificial intelligence may be used.

Providers of foundation models like GPT-4, the system underlying ChatGPT, “would have to guarantee robust protection of fundamental rights, health and safety and the environment, democracy and rule of law”, the Parliament says.

Ethical AI?! // Vilas Dhar (Patrick J. McGovern Foundation), Mehran Sahami (Stanford University), Navrina Singh (Credo AI), Laura Summers (Debias AI)

How Safe Is Your Job?

In their future-of-work bestseller The Second Machine Age, MIT researchers Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee predicted that professions of all kinds, from truck drivers to doctors and lawyers, would be impacted by machine learning and automation.

The dramatic shift in AI capabilities has upended the authors’ expectations, Brynjolfsson admits.

When the book was published in 2016, “we had this nice, pat understanding of the kinds of tasks that could be done well by machine learning”, the researcher – now at Stanford University – said at DLD Munich. “And a lot of that is flipped upside down.”

The EU-US Tech Gap // Zanny Minton Beddoes (The Economist), Erik Brynjolfsson (Stanford University), Andrew McAfee (MIT Sloan School of Management) discuss the impact of AI as well as Europe’s tech rivalry with the United States

But that’s no reason to fear a “job apocalypse”, the Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue. First, many tasks that can easily be automated may not even be worth human attention, they reason. Second, AI systems are hardly fail-safe at this point – so “in almost all cases, it’s going to be important to keep a human in the loop”, Brynjolfsson told DLD in a backstage interview.

“My mindset is not to fear these tools”, he added, “but to embrace them and think about: how can we use these tools to do our jobs better?”

Tina Klüwer, Director of the Artificial Intelligence Entrepreneurship Center, agrees. “We will have a new generation of workers who need to be familiar with those tools”, she told the DLD audience, arguing that people familiar with those tools are likely to have better job prospects than others. “And because of that, I would encourage everybody to get to know [AI] better, to study it, to try to use it, and not to ban it.”

Backstage Interview with Erik Brynjolfsson (Stanford University)

Boundless Opportunities

The Industrial Age was about mass production. With AI, the Digital Age takes another giant leap towards mass individualization. Whether it’s content, experiences, services or products: everything can be tailored to an audience of one.

“I think in a few years, we will find that almost all of our searches are generating content, with marketing copy, with photography, that has been modeled [specifically] for us”, predicts argodesign founder Mark Rolston. “So when I search for a pair of running shoes, I’ll see a 50 year old blonde man maybe running along the lake in Austin, Texas– and it’s been designed for me. No one else will ever see that image.”

Opportunities of Generative AI // Ina Fried (Axios), Mark Rolston (argodesign), Tom Mason (StabilityAI)

This will be thanks to AI models like Stable Diffusion, one of the most popular tools for turning text prompts into images.

“What’s happened in the last couple of years is that it’s been possible to take this enormous dataset and compress it in a way that’s extremely efficient and results in the models being very generalist”, explains Tom Mason, CTO of Stability AI, which developed the system.

And while “the baseline models are foundational”, as Mason points out, “it is the customization of them, and the personalization, that offers really big new opportunities.”

One example are companies that could benefit from tailor-made AI solutions based on their own data.

“At the moment, the data on which this stuff is getting trained is basically public data on the Internet”, investor Ludwig Ensthaler of 468 Capital says. Adding proprietary in-house data could supercharge the generic systems and result in something resembling an AI-powered X-ray machine for corporations, Ensthaler suggests.

Opportunities for the New Age of AI // Tina Klüwer (K.I.E.Z.), Jonas Andrulis (Aleph Alpha), Ludwig Ensthaler (468 Capital), Christian Teichmann (Burda Principal Investments)

“Just imagine you’re a manager and you can ask all the things about the interaction of your team efficiency, and so on or from your own data mixed with outside data – then I think that is going to be a massive application.”

What if the artificial brain gets a body, too? It needs to control body parts, develop a sense of its surroundings and make sure that nearby humans will always be safe.

“These systems are really trying to solve almost holy grails of AI, meaning manipulation, locomotion and interaction with the physical world”, says Sami Haddadin, Founding Director of the Munich School of Robotics and Machine Learning at the Technical University of Munich.

To achieve the goal, robots “have to be aware of their own body, of the other entities in the world and the environment”, Haddadin explains. That’s an enormous challenge and will likely remain a work-in-progress for years to come. Still, Haddadin is confident that his field of research will benefit from the rapid progress in AI.

“We want to address robots for society, robots for the grand challenges of our society”, he says. “And I think this synergy point at which we are at the moment – with the transformative characters of AI, communication, technology and robotics – opens up fundamentally new tools for mankind.”

Robotics & the Industrial Metaverse // Sami Haddadin (TU Munich), Quirin Görz (KUKA), Jennifer Schenker (The Innovator)

Who’s in Control?

It took ChatGPT barely eight weeks to attract more than 100 million users – setting a new record that illustrates how rapidly artificial intelligence is going mainstream.

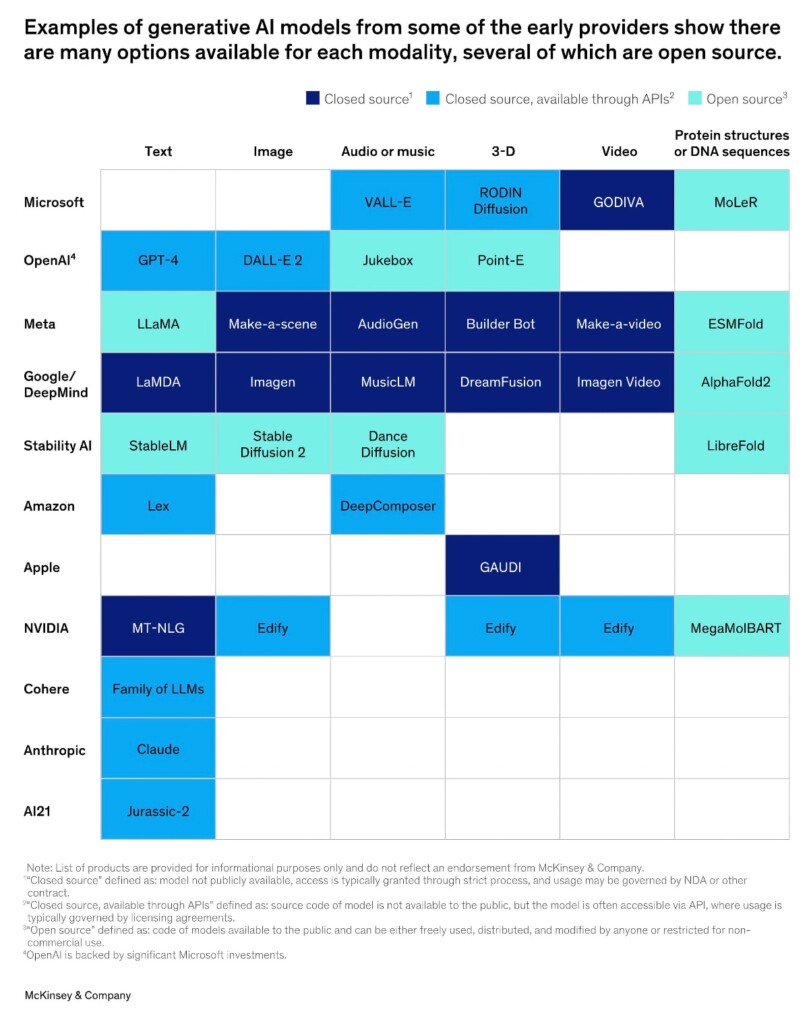

“The breakneck pace at which generative AI technology is evolving and new use cases are coming to market has left investors and business leaders scrambling to understand the generative AI ecosystem”, consultancy McKinsey observes.

As companies like Google, Microsoft, Open AI and many others keep adding features, the question becomes: are there any limits – and who sets the rules?

“As a developer, I want to see how far can we stretch the creativity with these AI tools”, Navrina Singh, founder and CEO of Credo AI says. “But also, as a member of the society, I think about, what are the implications if we don’t put the right guardrails in place?”

Generating excitement: This overview by McKinsey shows major players and what the generative AI systems are able to do.

Technologists often speak of an “alignment problem” because it’s hard to program specific goals and values – which align with desirable outcomes – into machine-learning algorithms. They’re meant to be flexible, adaptable and autonomous, after all.

“Artificial intelligence systems will do what you ask but not necessarily what you meant”, as the New Scientist puts it. “The challenge is to make sure they act in line with human’s complex, nuanced values.”

The alignment problem is a critical issue, Stanford researcher Mehran Sahami agrees. “But it ultimately brings up the deeper issue, which is one of governance”, he points out. “Who gets to choose?” Currently it’s the developers themselves, he says. “There’s no external governance mechanism.”

With his company Aleph Alpha, former Apple executive Jonas Andrulis aims to build a European AI champion that’s helping both companies and the public sector keep up with the speed of Silicon Valley.

“It’s important that we make this technology not only accessible to the most innovative corporations, but also to government”, Andrulis says. “And it makes sense that we are solving the modernization of our government technology with European AI.”

Open or Closed?

Meanwhile, in the race for market share, it’s far from clear who will pull ahead of the competition.

Microsoft-backed Open AI may have an edge right now, but even in the medium term, many observers believe, open-source systems – like Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion – stand a good chance to deliver similar performance at much lower cost.

“The dynamic of the open-source market creates a faster rate of iteration because there are many developers who are contributing to the market”, DLD regular Azeem Azhar recently noted in his Exponential View newsletter. Potentially, he reasons, “open-source models could learn and iterate far faster than closed-source ones.”

In a leaked Google memo, the anonymous author wrote: “The uncomfortable truth is, we aren’t positioned to win this arms race and neither is OpenAI.” Open-source models, he (or she) admitted, “are faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable.”

Regardless of who will win the race, understanding the technology, and how it’s used, will be key to achieving a positive outcome for society. Because otherwise, Mehran Sahami argues, algorithms will be in charge – not us.

“The more technology impacts our lives, and we don’t know about it”, he says, “the more, essentially, we’re outsourcing our decision-making processes to AI.”