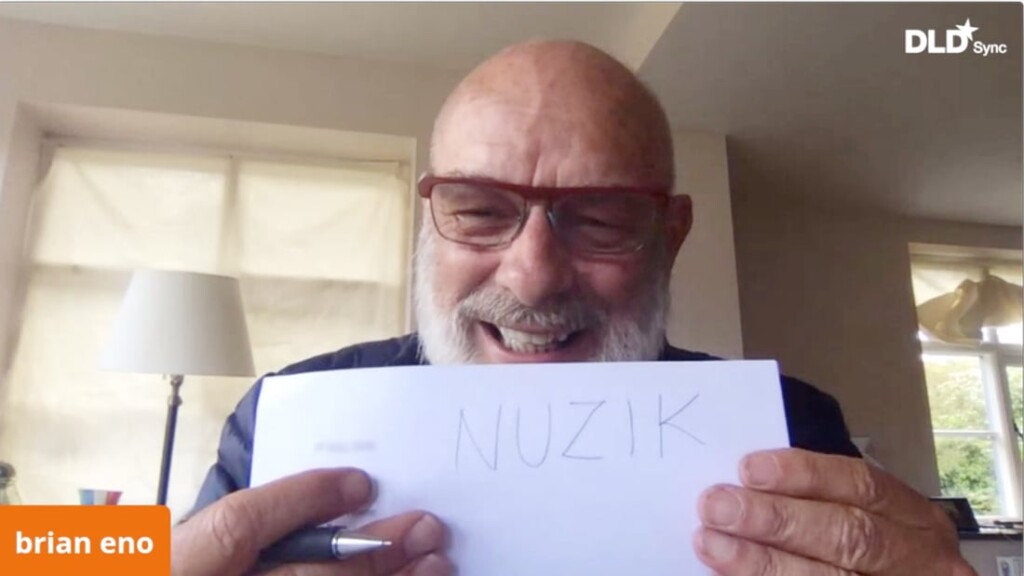

Listen To the Nuzik: Brian Eno on Art, Earth And Humanity

Musician Brian Eno is an eager explorer of connections between art, science and society. His DLD Sync session was full of wondrous insights and enlightening moments.

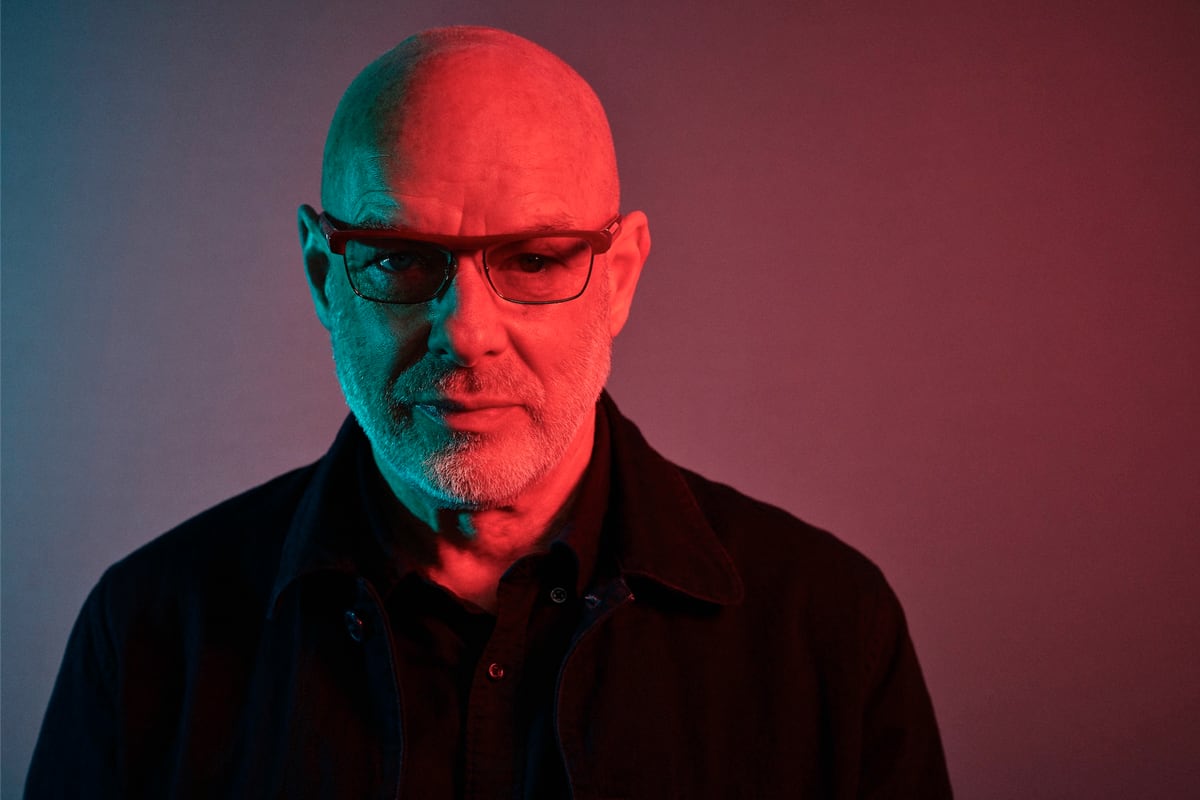

You may know Brian Eno as a founding member of Roxy Music, a pioneer of ambient music and the creator of the Microsoft Windows 95 startup sound. But the British composer is also an explorer of connections between art, science and society, always eager to look beyond the obvious.

His DLD Sync session with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Artistic Director of the Serpentine Galleries, resembled a journey across a vast, previously undiscovered continent, full of wondrous views and insights. The trip started with the composer’s role in the creation of musical landscapes, moved on to game design, science, climate change and social responsibility – only to end, appropriately, with sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll. You can view a recording of the full session below.

The Changing Nature of Music

Jazz, soul, rock, pop, electronica, hip-hop – from generation to generation, music shapes people and people shape music. But there was a watershed moment, some 130 years ago, when the art form itself was reinvented, Brian Eno believes. “Music that comes out of recording studios is in a way much more like a painting than like traditional music.”

While music lovers in the 18th century were lucky if they had a chance to listen to a Mozart or Beethoven performance more than once in a lifetime, “nowadays we can hear [a song] 7,000 times if we wanted to”, Eno observed. “Music is no longer fixed to time or to location.”

Add to that the ability to control every aspect of a record production and we really “should think about this art form quite differently”, Eno says. “It’s made differently, it uses different materials, it is listened to differently, and in different places. It’s no more like traditional music than cinema is like traditional theater.”

Suggesting that a new art form should also have its own name, he playfully proposed Nuzik. “It sounds like a product made of plastic, doesn’t it?”, Eno admitted with a laugh. “But I quite like it.”

Musician, producer, visual artist, activist: Brian Eno first came to international prominence in the early 1970s as a founding member of the British band Roxy Music. To date he has released over 30 albums of his own music and is a founder-member of the Long Now Foundation, a trustee of Client Earth, and Patron of Videre Est Credere.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is Artistic Director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. Prior to this, he was the Curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since 1991 he has curated more than 250 shows. Obrist’s publications include A Brief History of Curating, Project Japan: Metabolism Talks with Rem Koolhaas, Do It: The Compendium, Think Like Clouds and Ai Weiwei Speaks.

Steffi Czerny is Managing Director of DLD Media and co-founder of the DLD Conference as well as its global spin-offs. Steffi was identified as number 30 of The 2015 Wired 100 and has also been chosen as one of the 50 most inspiring women in European tech in 2015 by inspiring50.com for her success in bringing the international digital elite together at DLD.

Architect or Gardener?

As a pioneer of electronic music, Brian Eno came up with the term generative music to describe a new approach to composing songs. “Generative music is really the idea of creating a set of rules which then make music”, he explained in the DLD Sync session. “So the composer’s task is to design the rules and then let the system carry them out.”

There’s a fundamental difference to the traditional idea of what being a composer means. Think of it as being a gardener rather than an architect, Eno suggested. Traditionally, the composer has an exact idea of the musical building, using notes to describe every detail, Eno said, while generative music was closer to creating landscapes and planting seeds.

“The act of composing is the act of designing those scenes and designing the landscape in which they will occur”, he explained. “Then, once planted, you lean back and listen. You watch the garden grow. And if you don’t like the garden, then you change the scenes.”

“We’re All In This Together”

Born on May 15, 1948, Brian Eno turned 72 on the day he went online to Sync with DLD. Growing older, he told the audience, made him think not just about his own mortality but also of an existential threat to mankind.

If climate change were to continue unabated, the planet’s ecosystem might reach a tipping point in just 12 to 15 years. “I was struck by this coincidence”, Eno said. “The amount of time I have left in my life is probably about the same amount of time that the Earth has left in which to change its direction.”

He became uneasy with the idea of having an exhibition at London’s Serpentine Galleries centered around his work because he felt unable to devote the necessary amount of time “doing something that was just about me.” So he agreed with Obrist to change the whole direction of their planned collaboration. “I wanted the Serpentine show to be about the thought: ‘We’re all in this together. Let’s start the conversation!’”

To solve climate change and other challenges to survival, humans will need to take a collaborative approach, Eno believes. “The only way of creating complex enough systems to deal with the sort of future we might face is from the bottom up. [The solution] is not going to be designed by one person, it’s going to be designed by everybody.”

Giving Back

There would be no Internet, no GPS, no Amazon, Facebook or Google Maps without DARPA, a U.S. military agency that has been funding the development of long-term technology projects for decades. “A lot of those ideas start with tax payers’ money”, Eno observed – yet many tech giants built on these foundations try to minimize their tax obligations. In 2017, Amazon, for example, managed to pay less in taxes to the U.K. than singer Ed Sheeran.

“This has got to be a completely wrecked system”, Eno angrily exclaimed. He demanded that successful founders and companies should say, “We grew this out of the community and will give something back to the community.”

Letting Go

While the coronavirus pandemic has caused much harm, to people, countries and the world economy alike, it has also given us a chance to reflect on our lives. “We’ve all suddenly been discovering that we can live quite happily without a lot of the things we felt are essential”, Brian Eno observed. “It’s like a retreat – except the whole world is going on a retreat.”

The effect in society has been, to some extent, a healing of wounds, Eno argued, with political opponents cooperating rather than fighting – at least in the U.K. “Suddenly people have gone into a cooperative frame of mind.”

Asked about art’s role in a time of crisis, Eno responded: “Art is a powerful tool. It’s like fire. It can be quite dangerous as well.” Pointing out that infamous Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler was a passionate art collector, Eno added that “just basking in the glow of art doesn’t make you necessarily a good person.”

There can be no doubt, however, that art plays a crucial role in human existence, Eno said. “We don’t know of any human groups that don’t have art. It clearly does something important.”

Music in particular can have a calming effect on the soul, of course, as Eno’s newest album, Mixing Colours, which he recorded in collaboration with his brother Roger, illustrates. “I think it fits this moment”, Eno explained, “because it says, ‘Just calm down a bit.’ It sort of says: ‘Surrender to the moment.’”

To many people, surrendering is a difficult task, Eno believes, because technology, in particular, has given humans the ability to navigate their lives in a way that makes us feel safe and in control. “Control is not always possible, however”, Eno argues. “To navigate those [situations] we need to be able to surrender.”

It’s what Hippies used to call “going with the flow”, Eno pointed out, and what many people seek when take drugs, have sex or lose themselves in music. “The interesting similarity is that they are all situations where we find ourselves out of control, where we volunteer to surrender.”