“We Need Stories that Show Human Capacity for Action”

Harvard professor Martin Puchner describes how ancient links between literature and environmentalism offer insights for a better future.

Literature captures the thoughts, beliefs and values of different eras, making it a time capsule that preserves the cultural heritage of humanity. In bestsellers like The Written Word and Culture: The Story of Us, author, Harvard professor and public speaker Martin Puchner examines the contents of this time capsule – and shows how important it is to study the past in order to shape a positive future.

Sustainabilty is a core theme of Puchner’s book Literature for a Changing Planet, which looks at four thousand years of world literature to understand the cultural connections between intensive agriculture, urbanization and changing atttitudes toward the environment.

Ahead of DLD Circular, we spoke with Puchner about his findings. He explains why literature can be used as a “record of human attitudes toward the environment” and what we can learn from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels about effective storytelling as we try to find solutions for climate change and other challenges today.

What surprised you most when you researched your book, Literature for a Changing Planet?

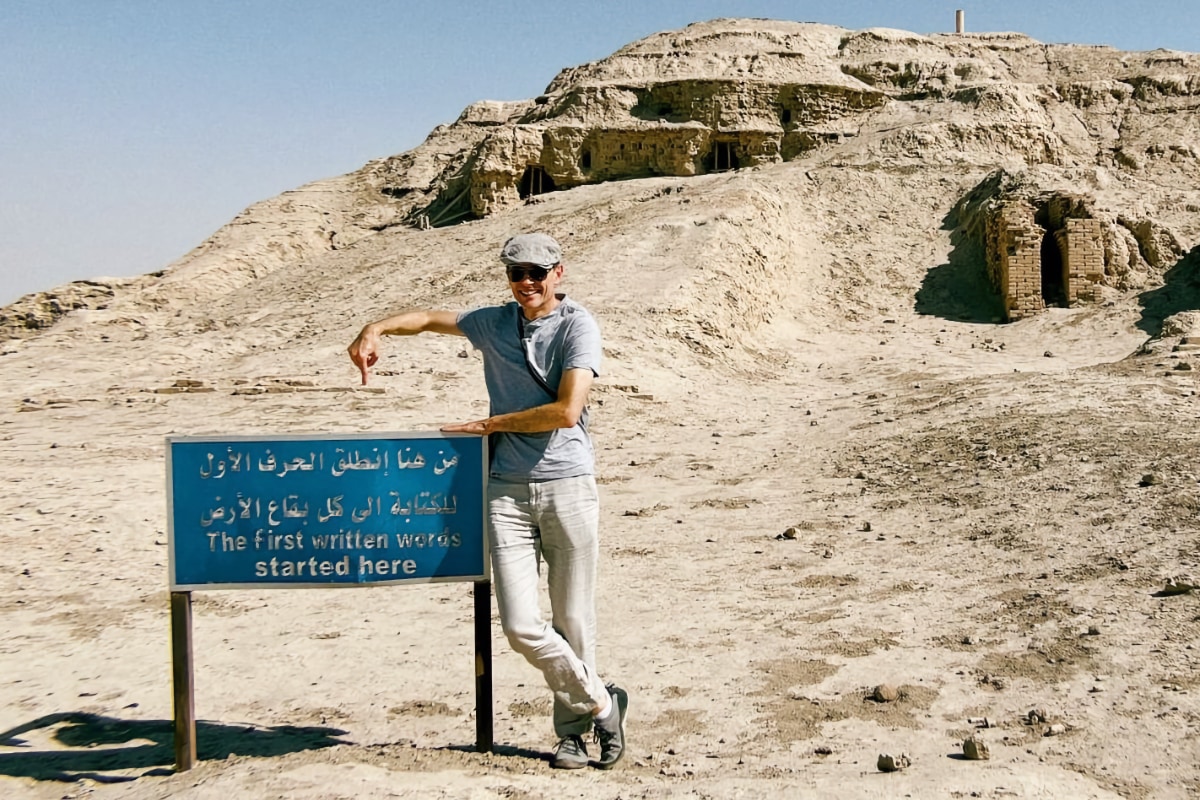

I was surprised by how deeply our attitudes toward the environment are rooted in cultural history. Before researching the book, I thought that the origin of the problem was the carbon economy and industrialization. But then I found that basic habits of mind, such as seeing nature through the lens of resource extraction, can be found in the earliest pieces of written literature, beginning with the Epic of Gilgamesh. This finding started to make sense only once I remembered that the Epic of Gilgamesh was written in the midst of the first urban revolution, and of the agricultural revolution that made urbanism possible. I have come away thinking that that’s the origin we need to go back to, Mesopotamia 5,000 years ago.

How can studying literature help us understand the effects of climate change?

Written literature can be used as record of human attitudes toward the environment. It can tell us when and how we came up with the idea of wilderness; when we started to think of nature as a natural resource; and how these ideas evolved and changed. You can follow it all in the written record, once you start looking for the evidence, almost like tree-ring dating.

DLD Circular 2023

This event was a transformative journey for all attendees on September 6, 2023, in Munich. Revisit DLD Circular 2023 to explore how the vision of circularity, combined with latest technological advances, can drive positive change in shaping a sustainable world.

Should we worry about doomsday scenarios from science-fiction books becoming real?

Like many people, I’m an avid consumer of doomsday books and movies – we humans seem to love that stuff. But as a researcher, I’ve become skeptical of them. They are not based on science but on stories, like the story of Noah and the Flood, that come from the reservoir of human apocalyptic imagination. I’m skeptical of these stories, also, because of practical reasons: they can instill inaction because all action seems futile; and they suggest a false sense of certainty. Uncertainty can be unsettling, so we sometimes crave certainty, even if it’s certainty of a terrible outcome. So, I think we need to ween ourselves from those doomsday stories as quickly as possible especially now when news stories about floods and fires seem to confirm doomsday predictions.

What common message did you find in vastly different books about the human impact on the planet?

I turned to the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Communist Manifesto for very different reasons. The Epic of Gilgamesh offers one of the earliest written records of resource extraction. I got interested in the Communist Manifesto not so much for its message as for its means of conveying it. When Marx and Engels were tasked with writing a program for the (tiny) Communist League in London, they invented a new form: the manifesto. It combined grand storytelling with an urgent program for changing history. It became one of the most effective texts in world history. I think we can learn from it as we face climate change and other challenges today.

What’s the power of literature? Can a positive narrative change people’s behavior?

Narratives, whether in the form of novels, movies, or journalism, shape how we view the world and our role within it – there is lots of evidence for that. The problem is that it’s very hard to engineer stories with a particular outcome in mind. This is why propaganda is often so deadly and futile. Powerful stories achieve their effects over time, by being told and retold by different writers and artists who adapt them to new genres and media. Having said that, I do think there are some lessons we can draw from history: one is that apocalyptic doomsday stories can induce apathy; another is that we need stories that show human capacity for action. There is a lots of scope for shaping the future – our stories about climate change should reflect that.