Entertaining the Dark Side: Iyad Rahwan’s “Evil AI” Cartoons

Can cartoons help us better understand the risks – and benefits – of artificial intelligence? Max Planck director Iyad Rahwan explains why he’s turning serious research into funny drawings.

What should a self-driving car do when it cannot avoid an accident? Save its passengers or hit the pedestrian – even if she’s crossing at a green light? Or in another scenario, should the car run into adults but always save the baby in a stroller?

This is the kind of moral dilemma that gives researchers sleepless nights. Iyad Rahwan decided to ask the public: When he was still at the MIT Media Lab he co-created the Moral Machine project, an interactive website that lets visitors decide how autonomous cars should behave in different situations.

Now the founding director of the Max Planck Center for Humans & Machines in Berlin, Rahwan has come up with a new project to address important technology issues in a playful manner.

On his Evil AI Cartoons website, he publishes funny drawings about serious questions that arise when humans rely more and more on clever machines – which might, one day, even be able to outsmart us.

DLD spoke with Rahwan about the origin of his new project, his intentions, and why, in fact, AI isn’t necessarily evil – but rather a tool designed by humans to pursue certain goals.

Why do you think the Moral Machine project resonated with so many people?

People like to think about these kinds of scary situations. It was a combination of this kind of fascination with the ethics of the dark side of decision making, and the outcomes and the dangers that might befall us. And on the other hand, artificial intelligence – and self-driving cars in particular – is a very hot topic. So it’s this very modern take on an old fascination. These two resonated together, I believe, and we provided just the right platform for people to engage with it.

Educating by entertaining

Iyad Rahwan, founding director of the Max Planck Center for Humans & Machines in Berlin, explains the pitfalls – and opportunities – of artificial intelligence on his Evil AI Cartoons website. He is also a co-creator of the popular MIT Media Lab’s Moral Machine project.

Speaker Profile

How urgent is it that we consider dilemmas that AI may create for society?

You’ll probably get different answers from different people about which dilemmas are the most important and when. I happen to think that if we engage with these questions early enough – and especially if we engage the public early enough, then we will be better able to understand what scares people, what their concerns are.

Most of us aren’t AI experts. Why should we think about these issues?

Because our expectations will shape what is built. They shape the decisions of the industry and will also influence the decisions of regulators. So I think it’s important to create an informed citizenry that is able to engage with these topics, that can process the public debates and the regulatory debate. And with the Moral Machine experiment, that’s exactly what we did. The primary goal was science. But at the same time, it’s played this educational and public engagement function, and I found that very rewarding.

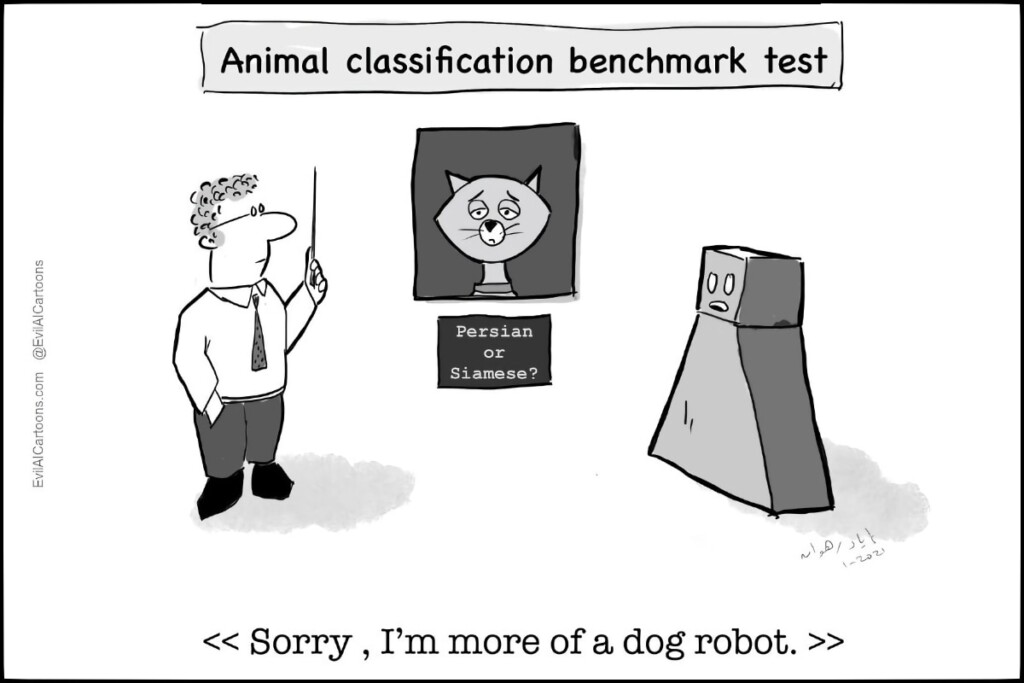

Catty answers: What if machines could not just recognize images but also understand what they see? (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

How did this lead to your cartoon website?

I wanted to continue to do science. But in parallel, I wanted to also have some venue for public engagement that’s different from writing editorials in magazines or giving interviews.

So you started to draw funny pictures about serious technology topics?

This project emerged somewhat organically during the corona crisis. My wife and I have two young daughters, and with all the lockdowns I needed some kind of hobby that’s pandemic- and family-friendly. I’ve always liked sketching, drawing and painting with watercolors. So I thought I’d pick that up again, and it’s something I can do at home and I could stop anytime and go and change diapers and come back.

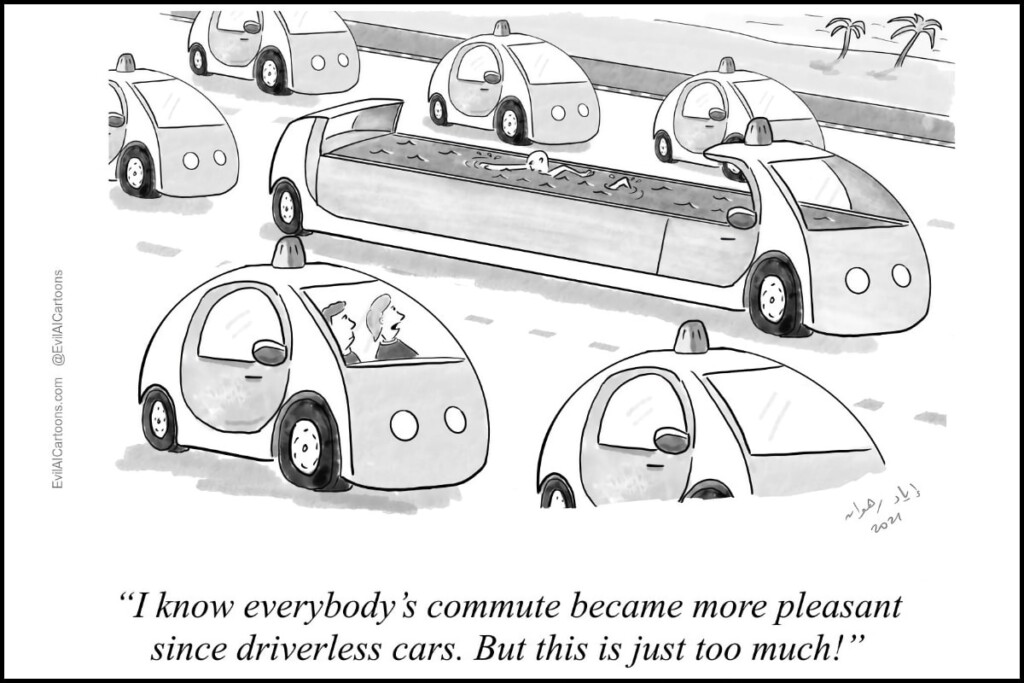

Floating in traffic: Why not have a swim when your car can find the way on its own? (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

Your cartoons could be out of the pages of New Yorker magazine.

I find the aesthetic of New Yorker cartoons very nice, with their single-panel approach and just one line of text. It’s a very strong constraint that forces you to be creative in how you deliver the message.

When did you decide to create a website for your drawings?

Originally they weren’t intended for the public. I would just show them to my colleagues. But slowly the project built up. I had some productive periods with four or five cartoons in one week. And all of a sudden, I had this big collection. So I thought, “Well, what to do with it?”

Iyad Rahwan

Max Planck Center for Humans & Machines

“How do you prevent another human being from building an AI that is not safe?”

Self-driving cars keep coming up in your sketches. What do you find so fascinating about them?

I feel the fact that everybody knows what a car does, and what an accident is, makes it much easier to engage the public with these kinds of complex topics. And for me, the car is also just an abstraction of any automated system. Because a lot of the questions I discuss apply in other domains as well – say, in medicine if we use algorithms for deciding who gets vaccinated first or who gets a ventilator.

Many of your cartoons address our fear of a super-human AI.

I think people are afraid, for obvious reasons. It’s the same reason we’re fascinated with, and worried about, things like climate change, global pandemics, an alien invasion or any other existential risk that we might face.

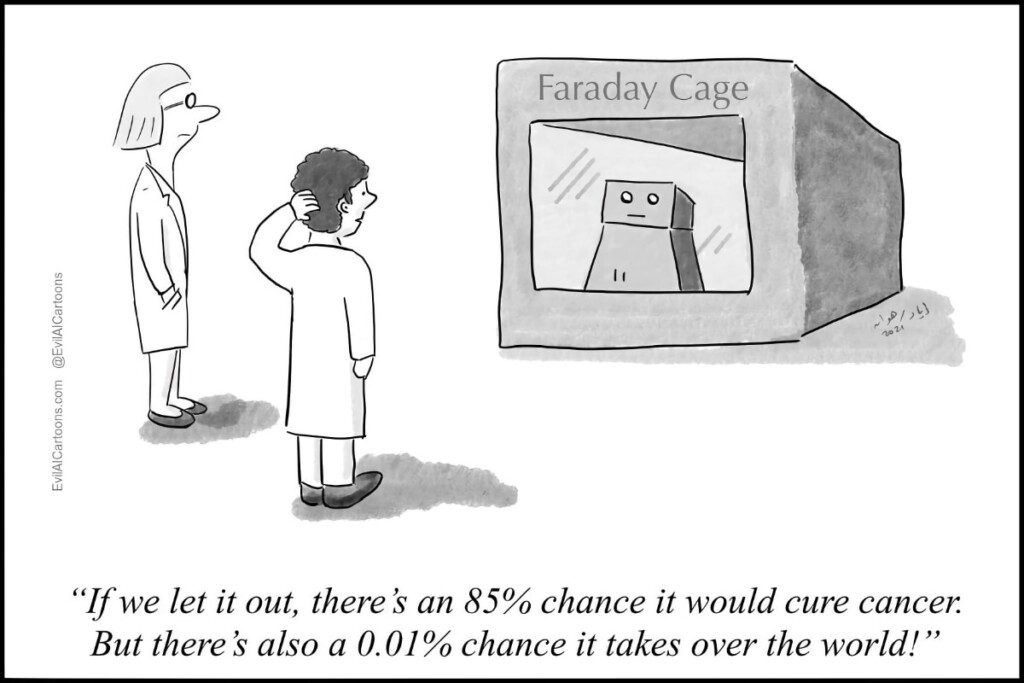

AI meets Atari: The challenge of keeping artificial intelligence in check is a recurring theme in Iyad Rahwan’s drawings. (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

Some of your colleagues are working on AI systems that by design cannot be harmful to humans.

I have much respect for these projects. At UC Berkeley, Stuart Russell’s research program on building provably safe AI is an inspiring goalpost. But I think in many cases it’s really hard to do that. How do you prevent another human being from building an AI that is not safe? It quickly becomes an arms control problem, or a global politics problem. So it’s not just a computational challenge.

What solution do you see?

It’s great to have algorithmic tools to build systems that are safe. And we do this with all sorts of systems, like train systems that minimize the risk of collision. But with artificial intelligence, the problem is so complex that we need all the tools at our disposal to be able to deal with this – including messy tools like politics and international diplomacy.

Iyad Rahwan

Max Planck Center for Humans & Machines

“We already have superintelligences today, and they’re not individual humans.”

How close are we to the vision of a general artificial intelligence that could outwit all humans?

I think we’re very far from having a single, monolithic machine that knows everything and is more intelligent than all of us humans. But we’re quite close to an alternative scenario where a superintelligence is augmented by machines. We already have superintelligences today, and they’re not individual humans.

Like what?

A corporation for example is smarter than any individual human being. It’s a result of coordination and knowledge exchange and the collective intelligence of groups of people – augmented with communication technology, norms and rules and so on. That could be the unit of selection in this new evolutionary race. Imagine corporations or governments gaining super powers by AI systems that are very specialized but extremely good in certain areas. They could be so good that nobody else can stop them. Now, is it the AI taking over? Well, it’s humans plus AI taking over – and I think that’s a more likely scenario than a superhuman AI alone.

Robo prison: Inside a Faraday Cage the machine would be cut off from Internet signals and helpless – but do really want that? (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

How do we stay in control of this development?

First, I think it’s important to not exaggerate the long term risks, so that people don’t push back against artificial intelligence in general. You could imagine, for example, people demanding a moratorium on AI research, and that would be a disaster. So we need success stories, we need people to see how beneficial this technology is for drug discovery or medical treatment or reducing greenhouse emissions.

Which role do you see for regulation?

Regulation often has at least two problems. One problem is that it lags behind, the other is that it can stifle innovation. My suggestion is that maybe instead of slowing down innovation we could speed up regulation – for example by having regulation and oversight powered by AI as well.

How would that work?

Setting the rules, designing the laws would stay in the hands of humans. But we could automate the implementation of new rules. So if legislators could get faster insight about where the problems are, thanks to better analytics, they would set the expectations, the human goals. And these goals would then be translated by programmers into AI systems that do the audit, do the process engineering or whatever is needed.

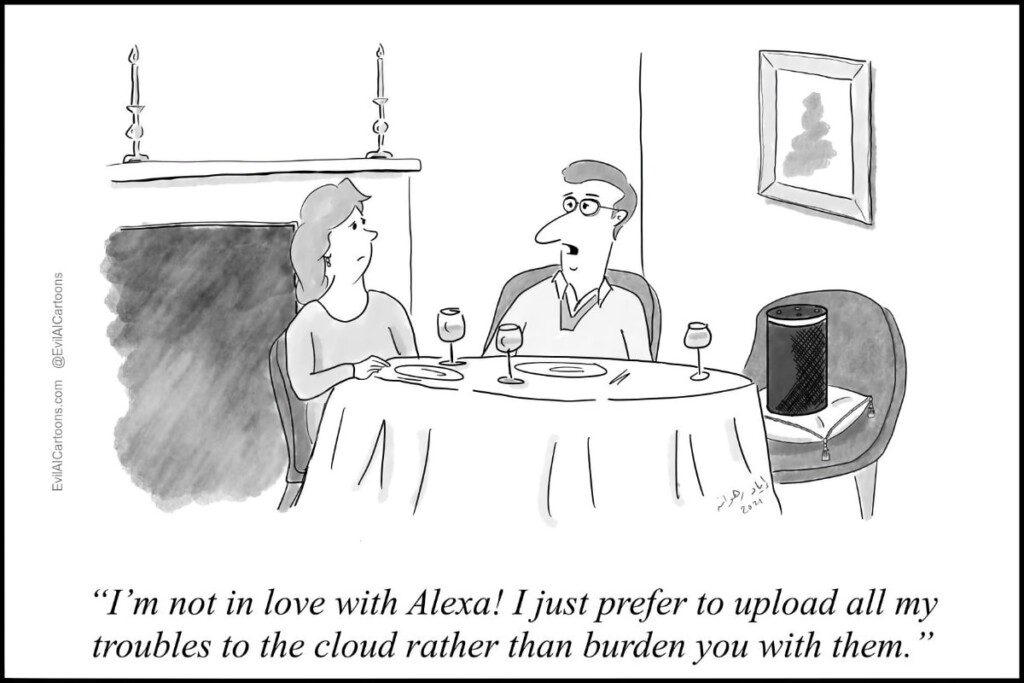

Making friends with AI: Does Alexa really deserve a prime seat at the dinner table? (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

Why do people who own robots often give them nicknames or treat them like pets?

My Alexa cartoon is mostly about a failure of human interpersonal connections rather than a triumph of technology. The fact that people are happy to confide in a fairly stupid robot, or a chat bot, is really telling us that this person doesn’t find another human being to listen to.

Maybe it’s also that machines are easier to deal with because they don’t they don’t argue with you?

That’s possible, yes. But people are using these devices already, even though they’re not good enough. Alexa is incapable of understanding me on the same level as another person. Having said that, there are domains – like behavioral therapy – in which an AI companion can be very useful. Not everybody can afford to have see a psychologist. So if there are bots that can help people overcome anxiety, reduce stress, deal with phobias and so on, this could democratize access to psychological health services. I think there’s a huge industry in the making at the moment, because of this.

Out of work: When machines lose their jobs to machines… (© Iyad Rahwan, EvilAICartoons.com)

One of the biggest fears related to AI concerns automation. How big is the risk that machines will make human work obsolete?

I’m not an expert in this area but the the emerging consensus is that automation plays a dual role. On one hand, it replaces some labor. But it’s not entire jobs. With very few exceptions, AI and robots perform rather specific tasks. And then what happens is, in most cases humans start doing complementary tasks to the machine. So there is a replacement process, but largely automation is about human augmentation. And the biggest challenge is to help people in the transition.

By re-educating them?

Yes, training is one example. Or having a universal basic income. There are so many different ideas. That said, I’m not a big fan of, “Let’s teach truck drivers how to program.” Not everybody can be a programmer – but they can be good at other things. And it may seem counter-intuitive, but our education system over the past 100 years has really been trying to make people more like machines.

How so?

We taught people to make very careful calculations, copy the table clearly, not make a mistake, adding and computing averages and so on. But now we have machines that can do these things really well. So I feel we need to teach people how to be better at being human. Interpersonal communication and relationship management, conflict resolution and strategic thinking – all sorts of things that are very important but also very hard for machines to do.

If you see so many benefits in automation and machine learning, why did you call your website “Evil AI Cartoons”?

Well, there is something of a threat, and I think that this is what’s primarily fascinating to people about AI. It’s the evil machine that’s going to come for us. So there’s a little bit of click bait, I admit, but it’s also meant to say, “Okay, you are afraid of AI. That’s why you came here. But actually, the evil is sometimes in the people, in the institution. And also it’s not all evil. There are good things, too, because AI creates all these opportunities to make our lives better.”