How to Make Sustainable Products “the Easiest Choice for Everyone”

There are smarter ways to do business than exploiting the planet. WRI expert Stientje van Veldhoven highlights the many benefits of rethinking the economy, for all of us.

There are think tanks, and there are “do tanks” – organizations that aim to change the world by engaging with politics, business, and society. The World Resources Institute belongs in this second category. Since its founding in 1982, the non-profit organization has pursued it its mission to protect the environment for future generations by operating on the principle of “Count it, change it, scale it”.

Ahead of DLD Munich 2026 (January 15-17), we spoke with Stientje van Veldhoven, WRI’s Vice President and Regional Director for Europe, about the need to change the current ways of doing business; why building a sustainable economy offers many opportunities to benefit both people and planet; and how sustainable products can become “the easiest choice for everyone” when they are no longer burdened with higher prices.

Where do you see the most urgent need for system change?

One of our most pressing challenges is land use. The combined surface we use for energy, feed, food and materials is breaking all planetary boundaries. That means we’re putting heavy pressure on the remaining natural reserves like land and water. One of the reasons for this disconnect is that our policies and legislation are inconsistent across different sectors. For example, we want to retain nature and woodlands as carbon sinks. At the same time we rely on forests and crops for building materials or biofuels. Europe should stop pretending it has endless access to land and develop a vision on strategic use of its land – for food, for nature, for feedstocks and for energy in a coherent way.

Stientje van Veldhoven

is the Vice President and Regional Director for Europe at the World Resources Institute, a global non-profit, science-based research organization. Van Veldhoven is a prominent politician in her native country of the Netherlands. Before joining WRI in 2021 she served as a Member of Cabinet responsible for Public Transport and Environment and as Minister for the Environment and Housing.

Speaker ProfileGlobally, many people worry about the state of the world’s rainforests.

For good reasons. Forests are incredibly important for our climate, biodiversity and the livelihoods of people – yet we keep clearing the Amazon and other tropical rainforests, largely for cattle ranching and other agricultural commodities. What many people might not know is that forests also drive rainfall, and not just locally. The Brazilian Amazon, for example, creates massive “rivers in the sky” that carry moisture and bring rainfall to crops across Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina. So when we lose 18 football fields of forest every minute, this is not only about trees being cut down, it’s about disrupting the systems that sustain our climate, our food, and ultimately, our well-being.

How can we better protect vital ecosystems?

We cannot consider the Amazon a natural park – it’s a region for millions of people to make their living. The same goes for Europe. The solution is to find a model, specific to each region, that helps people benefit from preserving nature rather than exploiting it. Fortunately, there are very good opportunities. Because if you truly start to appreciate the value of ecosystems, you can also rethink the economy.

DLD Munich 2026

A world of change is a world of opportunities. From January 15-17, you’ll get the chance to see and meet some of the most creative innovators in the world. DLD Munich 2026 brings together scientists and CEOs, inventors, founders, investors, politicians and creative minds from all over the world. Join us to discuss bright ideas for the world of tomorrow, make friends, and find new business partners. Our promise: “It’s gonna be wild!”

What would that look like?

Let me give you an example from WRI’s work around the world. In Indonesia, the food, land, and water sector makes up about 25% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s also the source of income for millions of people and the foundation of Indonesia’s food security. We are working with partners to transform this sector in practical ways. One example is the use of cassava, which is also known as the “Rambo root.” It’s very resilient, can revive unproductive land and pave the way for other commercial crops. It also strengthens soil structure, improves water infiltration and reduces erosion. This means cassava can help protect primary forests while boosting rural incomes. Trials in Vietnam showed that farmers could increase their yields by up to 400%. This higher productivity reduces the pressure to clear forests.

What about Brazil and the Amazon?

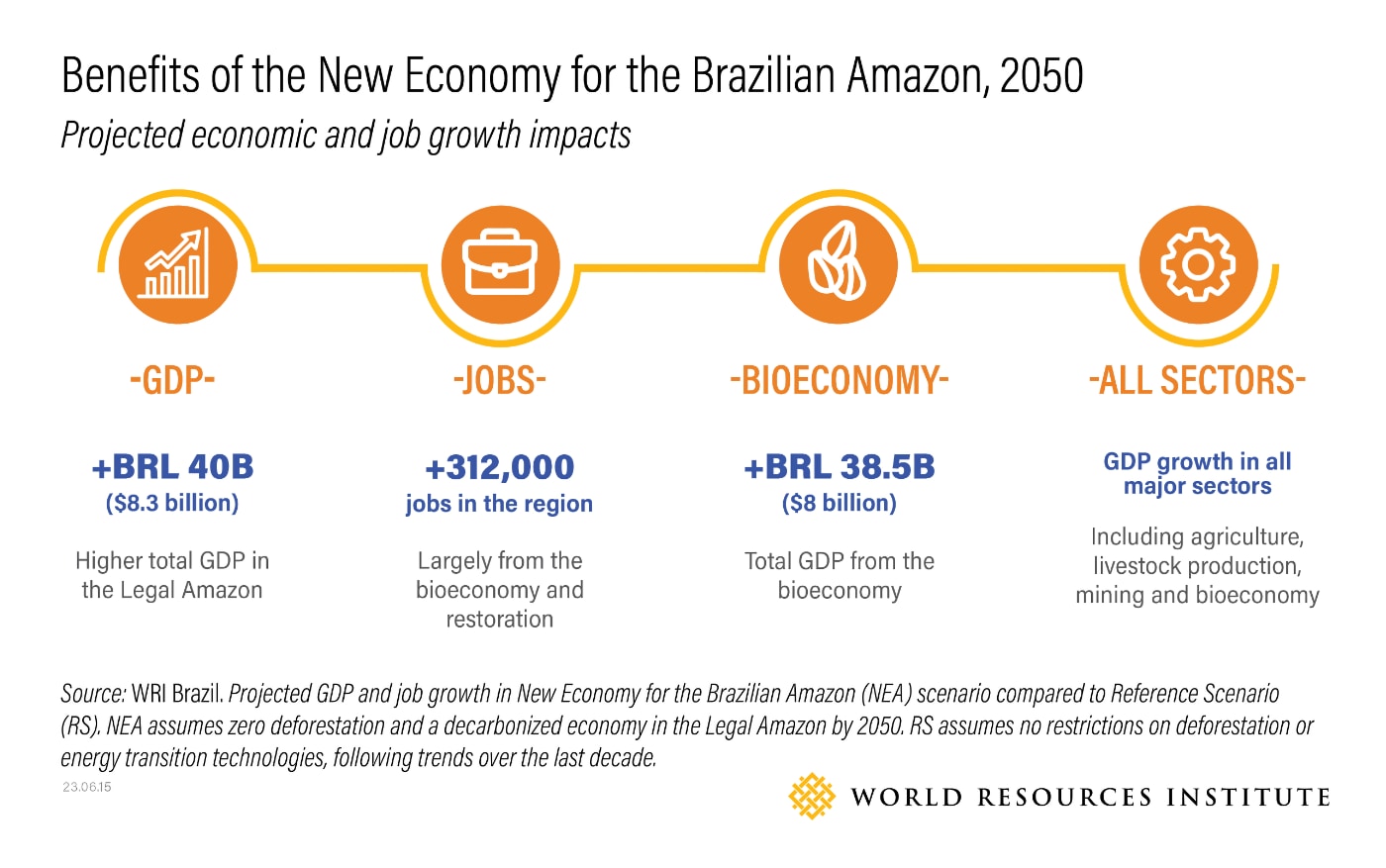

For Brazil we calculated a new economy for the Amazon. This was in collaboration with about 300 scientists from that region, as everything that WRI does always happens in partnership with many others. And if you look at the economic growth that Brazil can get from a standing forest, it’s so much more than from cutting down the trees. The transition to a low carbon, deforestation-free Amazon economy could add around $8.3 billion by 2050 in annual GDP growth, without significant cost to the economy. When you look at the benefits, not only for Brazil but for the region and the world, it’s really a win-win for everyone.

Natural benefits: The WRI report “New Economy for the Brazilian Amazon” illustrates the potential for economic growth by protecting the rainforest.

What does this “new economy” for the Amazon look like?

We showed that more than 300,000 new jobs could be created through expanding the Amazon’s bioeconomy, investing in regenerative agriculture, and maximizing the potential for clean-energy production. But for all of this to work, we need to make sure that countries like Brazil or Indonesia see a direct benefit from change. The fragile balance in a tropical forest cannot support highly intensive production methods; more value will need to come from less volume. This means that producing countries should be supported to move up on the value chain. For example, not just exporting the raw Acai for international companies to profit from, but to turn them locally into higher value products.

Are you confident that consumers in industrialized nations are willing to pay higher prices for more sustainable products?

The price of what we see in the supermarket today is the result of standards we set for the production of goods. We’re used to pricing in the cost for things like energy, materials and labor. And we’re only starting to realize now how climate and nature fall into the same category. Yet our system still incentivizes practices that damage forests, nature, and the climate – even though it would be far less costly to prevent this damage than deal with the harm it’s causing.

Stientje van Veldhoven

World Resources Institute

“Sustainable solutions seem ‘uneconomical’ only because markets are not designed to recognize their long-term value.”

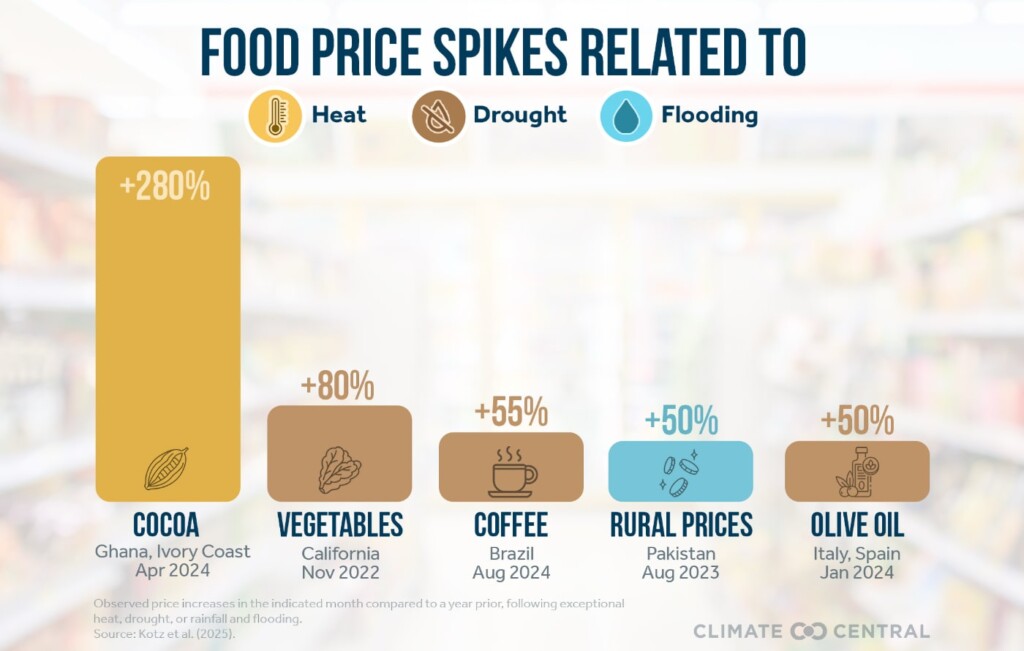

The European Central Bank recently calculated that about 75% of all corporate loans in the Euro zone are granted to companies who rely on one or more ecosystem services. Imagine what would happen if aquifers ran dry and if water must be desalinated – which is a very costly process. We already see food prices rising due to changing weather patterns and droughts, and for items like chocolate and coffee, for example, there’s a direct link to biodiversity loss, deforestation, and the effects of human-made climate change.

What should be done to make the hidden costs of damaging nature more visible?

Sustainable solutions seem “uneconomical” only because markets are not designed to recognize their long-term value. This is where governments, Central Banks, re-insurers, and pension funds can play a major role – by setting better incentives for the long-term optimization of the use of natural resources. Governments and cities also play a major role, because they can build bridges between the short and the long term through public procurement and creating more sustainable market demand. Lasting change will come from reshaping the entire system, so that sustainable products become the easiest and most affordable choice for everyone.

Heat, drough and flooding are driving up the prices for many food items, including coffee, vegetables and cocoa, the basis of chocolate. (Source: Climate Central)

Is this more than wishful thinking?

We actually have experience doing that. The Montreal Protocol from 1987 is one of the clearest examples of regulation that changed things systematically and led to innovation. It brought nearly every country together to phase out CFCs, the chemicals harmful to the earth’s protective ozone layer. Industry developed new cooling technologies and safer refrigerants, which had two benefits: the ozone layer is now recovering, and consumers got more energy-efficient, reliable products. This shows how well-designed environmental policy can guide markets, create a better future and deliver products that are much better for all of us.

What’s the best way to design this kind of regulation?

One way to make not just regulation, but the entire economic system work, is by properly accounting for the value of nature in our economy. A key part of that is understanding the financial risk of not investing in its protection. Half of the world’s GDP depends heavily on nature, and by 2050, nearly a third will be exposed to high water stress. Yet we still channel about $7 trillion each year into public and private investments that directly harm nature. No business will thrive on a dead planet. The sooner we realize that and reflect it in our balance sheets, the sooner we can redirect finance and regulation towards protecting nature.

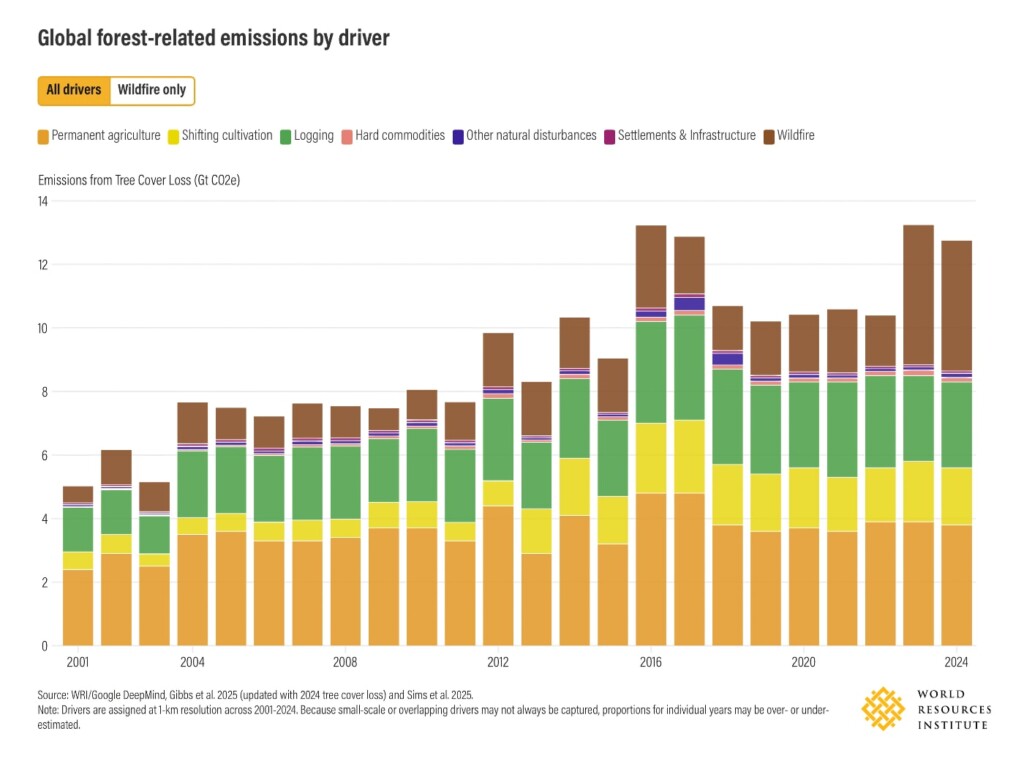

Analyze this: Satellite data helps WRI monitor the health of the planet and collect vital stats, such as forest-related emissions of greenhouse gases.

What role does technology play?

Technology can help in monitoring and implementing these efforts. Tools like Aqueduct help us evaluate water risks and support planning decisions. With satellite monitoring, we are now able to document the state of forests all over the world almost in real time. WRI developed an online tool for this in 2014, called Global Forest Watch. We have tracked deforestation for a long time, but now with both AI and satellites becoming much more readily available, the resolution on which we can make these observations is much, much higher. This year we launched a tool called Global Nature Watch that tracks grasslands, vegetation and other forms of land use. So you can actually see what’s happening for each plot of land, let’s say a coffee plantation, and see if there were trees yesterday or if it’s expanding and if there will still be trees next week.

Who is using Global Forest Watch, and to what effect?

The tool is used in many different ways. As a company you can use our imagery to support your claim that your product has not led to deforestation. Researchers and journalists use our data to trace, for example, forest fires and their impacts. Foresters and governmental departments use it to calculate the volume of potential “firewood” – meaning highly flammable material that could ignite forest fires in a given region. This helps prevent and combat wildfires more effectively.

Any other examples?

Illegal logging remains a major issue. Through satellite monitoring we can very quickly detect it; an indication is the construction of roads which will be used to get those massive trees out of the forest. This is clearly visible from space, and monitoring allows for indigenous communities and local authorities to be alerted in time and make efficient use of limited enforcement resources to combat illegal deforestation.

Our tool is also very useful in the context of agriculture. We can measure how grasslands are changing over time, whether from degradation or conversion to other usages. It can help farmers be much more efficient with the fertilizer they use or to keep track of how their land is doing, how ecosystems are improving or are deteriorating. So this kind of imagery is crucial in managing our natural capital well – and that, in return, is essential for the wellbeing not just of our planet but for all of us, around the world.