Turning Cancer Against Itself

Californian startup Earli aims to outsmart one of the world’s deadliest diseases by combining biology, engineering and software. CEO Cyriac Roeding shares details with DLD.

With cancer, time is of the essence. The sooner a potentially deadly tumor is identified, the better a patient’s chances of survival. “Significant improvements can be made in the lives of cancer patients by detecting cancer early and avoiding delays in care”, the World Health Organization notes.

The trouble lies in cancer’s complexity. For one, it’s actually not one disease but rather a diverse group of diseases, each with unique genetic and molecular characteristics. In addition, many forms of cancer are very hard to detect.

Enter Earli, a Californian startup with a novel approach to both finding and treating cancer early.

Co-founded by the late Stanford cancer researcher Sam Gambhir, David Suhy and Cyriac Roeding, the company is working on a method to program cancer cells in such a way that they reliably show up in computer tomography scans – and even wants to make tumor cells kill themselves.

A Moonshot in the History of Medicine

“It’s a moonshot”, Roeding admits. But if it works, “it’s going to change everything”, he believes, “because for the very first time, we are taking control of the cancer rather than letting the cancer dictate what it wants to do to us.”

Ahead of DLD Munich 2025, we spoke with Roeding about his company’s groundbreaking technology, the implications for cancer therapy, and why medicine in general is at an inflection point. Join us from January 16-18, 2025, to get insights from more than 180 expert speakers and meet fellow innovators from around the world. Apply for your ticket now.

Cyriac Roeding

is a serial entrepreneur and CEO of Earli. Born in Germany, he now lives in California. After selling Shopkick, a mobile app that he co-created, Roeding became interested in the work of Stanford researcher Sam Gambhir, one of the world’s leading cancer experts. In 2018, they launched Earli together with Dr. David Suhy. Gambhir tragically died of cancer in 2020 – just like his wife and son. “We need to carry Sam’s torch”, Roeding says. “We must make this work for millions of people who need to become more fortunate than Sam, Aruna and Milan.”

Speaker ProfileHow does Earli aim to cure cancer?

The holy grail of cancer treatment is to kill the bad cells without harming the good cells. That is incredibly difficult to do because healthy growth and malignant growth are so genetically intertwined that unbraiding the two might be one of the most significant scientific challenges faced by our species. But that’s exactly what we’re aiming to do at Earli.

What makes your approach different?

Pharma companies have spent billions of dollars trying to find natural biomarkers – signs of abnormal processes – on the outside of cancer cells in order to develop drugs that can specifically target these cancer cells. But the problem is that most cancers don’t have these biomarkers on the outside of cancer cells, and even the few cancers that do have them don’t reliably produce them for all patients.

Because after all, cancer is a mutation of your own cells. Therefore the tumor markers are also mutating all the time, which means there is no cancer drug that works for all patients. Pharma companies have responded to this challenge by trying to develop drugs for ever smaller sub-groups of patients; each of these efforts costs over a billion dollars and takes 12-15 years, and most of them fail nevertheless.

Earli came about through Stanford University and the work of the late, great Sam Gambhir, one of the world’s leading early cancer detection and treatment experts. At one point Sam said, “What if we stopped searching for natural biomarkers altogether? What if instead we could use a genetic construct that flips on like a light switch when it’s cancer, but does not flip on when the cells are healthy?”

How are you trying to make this work?

In simple terms, the idea is to target the nucleus of tumor cells, where disease-causing mutations happen, and force the cancer to produce a protein of our choice. This protein could then be used for imaging – to find and diagnose the tumor; or it could be used as a messenger protein, a cytokine, to activate the immune system in order to attack the tumor and ultimately kill it.

In other words, this would be the first synthetic target platform where we control what the cancer does, and not the other way around. And it would be the first synthetic target platform that has ever existed. That’s what Earli does.

DLD Munich 2025

For its 20th anniversary, DLD brought together more than 180 speakers from science, business, politics and culture. You can revisit this fantastic event our conference page, which as photos, videos and a list of speakers. To keep in touch and learn about future events, please sign up for our newsletter.

What’s the trick to making only cancer light up?

There are several elements to making this work. The first one is a nucleic acid template, which you can think of as a cargo container for genetic content. Inside the cargo container, we are adding an if-then clause: “IF cancer, THEN make something.”

The “if” part is a synthetic promoter, a genetic sequence that activates in the vicinity of mutations that can cause cancer. The “then” part is a protein that can bind to a radioactive contrast agent, which shows you where the tumor is in a PET image. Or it can be a protein that activates the immune system against the cancer.

Sounds almost like a digital approach to healing cancer.

Think of Earli as a techbio firm, not as a biotech firm. This a big difference because we’re applying principles of engineering to the world of biology, and we’re rapidly iterating. We’re using the intersection of biology, engineering and software to create the next generation of cancer treatments.

Our approach requires very detailed knowledge of individual cancer mutations. We need to identify the specific mutations of tumor cells so that we can deliver our programmable genetic vectors in a highly targeted way.

Cyriac Roeding

Earli

“We used machine learning and artificial intelligence to analyze over 20,000 fully sequenced cancer samples.”

To do that, we decided to look at the downstream effects of evolving tumors, such as rapid cell proliferation and lack of cell death – the hallmarks of cancer. We then used machine learning and artificial intelligence to analyze over 20,000 fully sequenced cancer samples. It was so much computing power, we needed to rent four of the largest instances from Amazon AWS for an entire month to run through the data for one cycle.

This gave us a list of signs to look out for, indicating that a patient may have lung cancer. We started with lung cancer, because this is the biggest killer. Twice as many people die from lung cancer as from colon cancer, the second biggest killer.

Earli’s approach explained: Watch the video to find out details about the company’s novel approach to cancer therapy.

What is your success rate?

We’re now at a 98% detection rate on individual lung cancer cell samples taken straight from Stanford Clinic’s operating room. It took us five years and $60 million to get to this point. That sounds like a lot of money, but it’s actually very little compared to what the pharmaceutical companies have been trying to do for decades; considering that they’ve been spending billions of dollars on cancer research.

Have you started clinical trials yet?

We did a safety study in Australia, and the results were good. The next step is to show the efficacy of our approach in humans, in a phase one and phase two study. That’s what we’re raising money for now.

Our investors know that Earli is a moonshot. When we first started the company, I told Andreessen Horowitz, “It has a 5% chance of working. But if it works, it will change everything.” Because for the very first time, we are taking control of the cancer rather than letting the cancer dictate what it wants to do to us.

Still, they invested. Two years later, I told Khosla Ventures it has a 20% chance of working because we had made some progress. They came on board.

Now I personally believe we might have a 60% chance of success because we found an approach which gives us the chance to get into the nucleus of the tumor cell and trigger an accurate response.

That’s the holy grail of cancer. But we still have to bring it to consistently high output. And we have to bring it to humans. So we’re definitely not at 100%, but we’ve come much further than probably most people expected.

Cyriac Roeding

Earli

“We’re working on the therapeutics part as well, where we’re manipulating the tumor itself, to kill it, to turn it against itself.”

When are the clinical trials starting?

We’re planning to be in humans in a little bit over a year, in early 2026. In parallel, we’re working on the therapeutics part as well, where we’re manipulating the tumor itself, to kill it, to turn it against itself. This is how we describe Earli’s mission in a nutshell: “Turn cancer against itself.”

Could your approach be applied to any type of cancer?

I believe that the era of bioengineering cancer against itself is the next big era of cancer treatment and detection. The oncology field has gone through various phases of cancer treatment. It started with surgery, then we went on to chemotherapy and radiation. In the past 20 years, immunotherapy has seen a breakthrough, which supports a patient’s immune system in fighting cancer.

All of these were huge steps forward, but in all of these, we were dependent on what nature gives us. If the cancer provided some signal that it is cancer, then we might be able to react to it. Otherwise, we could not.

In the next era, we will be able to take more control of the cancer. And the best way to do that is with engineering approaches, with bioengineering, where we start to understand what the cancer is, and then flip the table and turn the disease against itself.

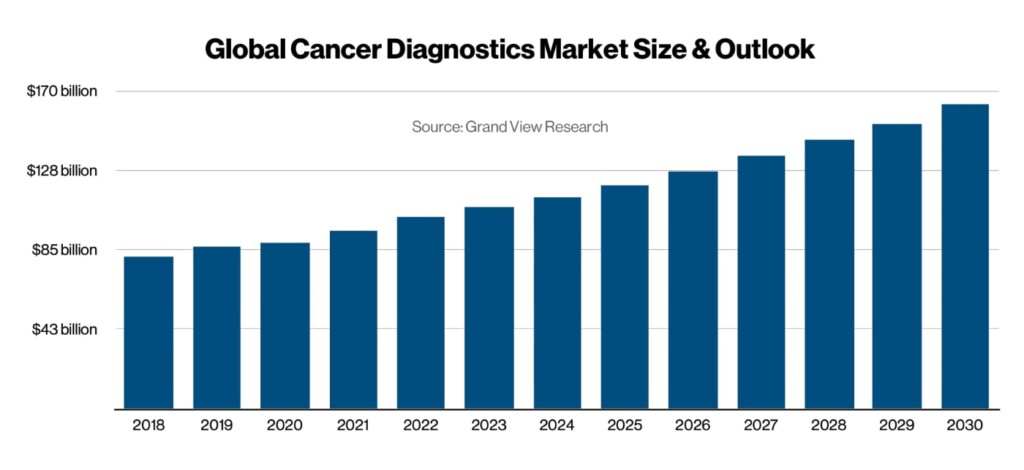

Business outlook: The worldwide cancer diagnostics market is projected to grow to $162 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research.

Are we at an inflection point in medicine?

Absolutely. That’s why we’re currently seeing an explosion of new approaches, made possible by the combination of biology, engineering, and software. Now that those three worlds come together, there are new ways of treatment that were unthinkable before.

Every time AI advances in an exponential fashion, we are going to exponentially benefit from that in the life science world, in the world of medicine, across cancer and other diseases, autoimmune diseases, chronic diseases. All of them require new approaches.

And for the first time, we’re starting to understand step by step what the genome actually means. If we call the genome the “language of life”, then really, if we’re self-critical, we’re only at the stage where we can understand that the DNA is the “alphabet of life.“ It has four characters, and it constantly permutates in different combinations.

Cyriac Roeding

Earli

“One day, we will suddenly understand words, sentences, grammar structures in the entire book of life.”

But we don’t understand words, sentences or grammar structures, let alone paragraphs or chapters of the book. Yet step by step, we’re starting to understand that if we manipulate this one character, then the book suddenly has a different ending. And if we manipulate another character, then this happens, and so on.

Now enter AI. You feed all of these insights into a machine that learns from them and starts recognizing patterns.

To what effect?

As with all exponential developments, the curve may look flat in the beginning, and you almost feel like you’re making no progress. But in reality, this whole thing is slowly but surely growing. And all of a sudden, like with any exponential development, it takes off like a rocket because you’ve reached critical mass.

One day, we will suddenly understand words, sentences, grammar structures in the entire book of life – what’s a verb, what’s a noun, and paragraphs. After that, we will understand whole chapters, and finally the book itself.

For the first time in life sciences, we are starting to engineer the system. We’re starting to understand and then manipulate, and understand and then modify, and then create. Those are the steps. And we are on our way now. That’s why I’m doing what I’m doing.