Business in the Exponential Age: “You Have To Take On More Risk”

In this DLD interview, Azeem Azhar, author of “Exponential”, explains why change keeps speeding up – and what all of us can do to master the challenges ahead.

The digital age is morphing into the “exponential age”, with rapidly evolving technologies intersecting, overlapping and empowering each other. Few people have studied this phenomenon more deeply than Azeem Azhar, who launched his popular Exponential View newsletter in 2015 and has now published his observations in a book, Exponential: How to Bridge the Gap Between Technology and Society.

DLD spoke with Azhar about his most important insights and how companies, individuals and society can best deal with the constant disruption that rapid change brings. To watch Azeem Azhar’s DLD talks please visit his speaker profile.

Azeem Azhar is the writer behind Exponential View which explains how society and the political economy are changing under the force of technology. Subscribers include investors, academics, and journalists around the world.

How are chewing gum sales related to smartphones?

Quite often, when you’re in a store there will be small bins of chewing gum or other candies – right at the checkout counter. And while we’re waiting we’ll pick one of these up and pop it in our basket. But within a few years of the ubiquity of the smartphone phone in the United States we saw a drop in the sales of chewing gum. One hypothesis is that when people are glued to their screens they aren’t noticing the tasty chewing gum as much.

What can companies learn from that example?

I think one of the hardest things about doing business in the Exponential Age is being able to understand what the second or third order effects of disruptive innovation are. And one key element is that you need to be critical about your own business: what really is the job that you’re doing, the service you’re providing? In the case of chewing gum, the job it was doing at the checkout counter was really not about the gum itself – it was about our boredom.

Is it possible to foresee the consequences of such feedback loops?

It’s difficult for businesses to use traditional ways of looking at opportunity and threat when you face these fast changing markets. But companies who develop the muscle to understand disruptive technologies are usually the ones who show the ability to navigate these changes. The question is whether you decide to be the recipient of fast change, or whether you prefer to be part of the action.

What does that mean in practice?

You have to take on more risk. You may get certain things wrong, and your timing may be off, but it’s important to lean in. When you have technologies that are declining in price at 20 or 30 percent per annum you can’t argue that cost is making a transformation unviable. The exponential drop in prices will make that rationale disappear fairly quickly.

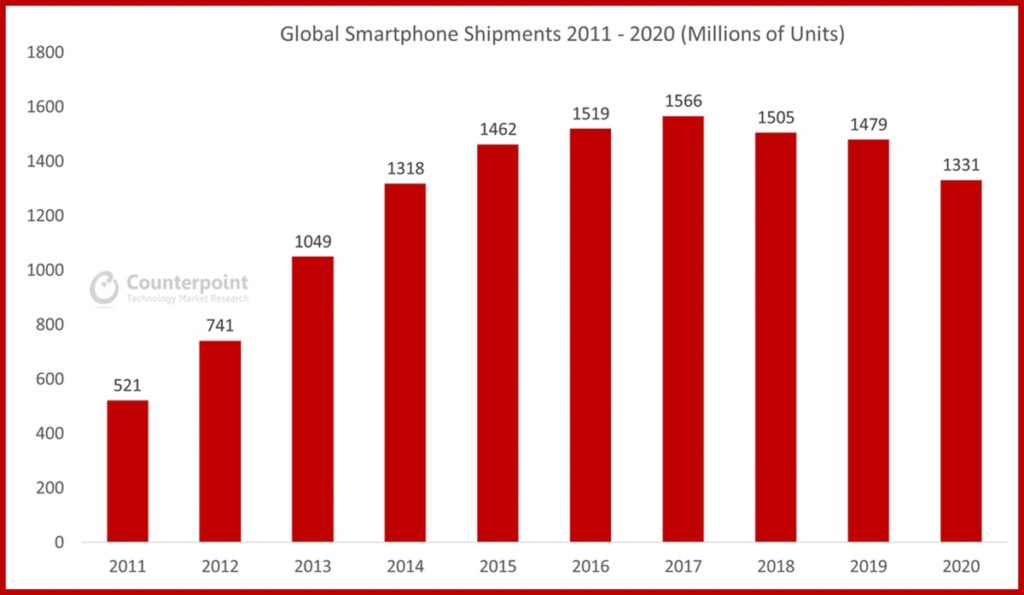

Smartphone sales followed a typical exponential growth curve before leveling off when the market got saturated, as data compiled by Counterpoint Research shows.

We’ve seen exponential growth for decades, particularly in computing. What is different now?

I believe we are entering a new phase because this time the exponential shift is not happening over centuries or generations. It’s happening over the course of a decade or less.

What’s driving the acceleration?

In the early years of the computer industry, the number of people, the number of industries that were actually impacted by exponential change was quite small. Whereas today, with billions of us having smartphones, technologies that are improving exponentially can affect really large numbers of people and businesses very, very quickly. The result is that in many areas, technologies create an environment very different to the economy that we had in previous decades. If you look at capital markets now, what they value most is Exponential Age firms: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Tencent.

Azeem Azhar

Exponential View

“We have to recognize that some companies will end up dominating certain parts of the economy.”

What makes these companies special?

The Exponential Age creates what I call “unlimited companies” in many sectors: companies that can grow very, very large and very dominant. We have to recognize that some companies will end up dominating certain parts of the economy.

How should lawmakers respond?

A new age needs need new rules. We’ve come from 100 years of business orthodoxy that essentially says: in most cases – unless there is some form of bad behavior – markets remain competitive. But those were the rules of the Industrial Age. Unchecked power is problematic, so if we think that companies naturally tend towards these positions of dominance, then we need to find ways of checking their power.

What do you suggest?

One idea is that companies should be mandated to interoperate, to open up. For example, right now, when you are on Facebook you can’t post content to TikTok. And if you’re on TikTok, you can’t check in on your friends on Facebook. We’re forced into these different silos. The Internet didn’t use to be like that. It was very open, and what that does is it puts power back in the hands of the end user.

Meet the Zucker Net: More than half of all Internet users regularly use Facebook, according to Statista. The humble beginning of Mark Zuckerberg’s social network is barely visible in the chart anymore.

Even if we could more easily move from platform to platform, that wouldn’t reduce the power of the tech giants, would it?

Another idea is to treat companies that get bigger and bigger like essential utilities, in the way that we think of our water network or sewage network or power system. So if there are aspects of a technology company’s business operations that are essential to the economy or society as large, we should demand the highest standards of reporting, rules around equivalent access, and in some cases, rules around the level of profit that can be made from these utility operations.

You say that we’re only at the beginning of the Exponential Age. What shifts do you anticipate next?

Within the technology domain we see four areas with general purpose technologies that are getting cheaper and cheaper and cheaper: computing; our ability to tinker with biology and learning from nature; our provision of energy; and the way in which we will end up manufacturing things. And every one of those is declining on a price-performance basis by about 20 percent minimum per year. In some cases 30 percent, 45 percent or even faster.

What impact could that have?

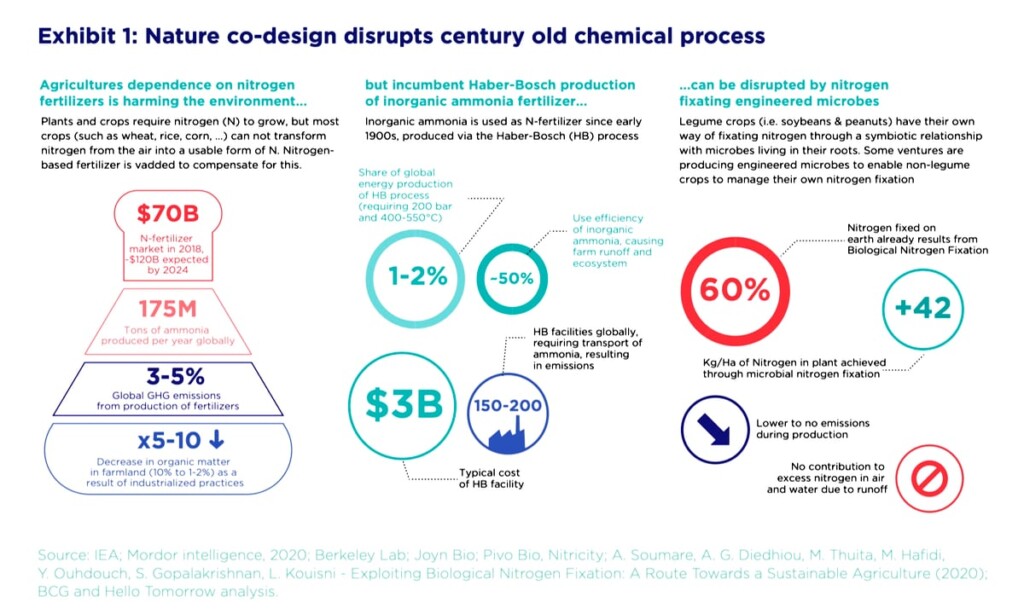

Take synthetic biology: Nature is full of amazing materials. Wood is solid and strong but also light. Spider silk is stronger than steel. Plants fix nitrogen out of the atmosphere without needing to use high temperature or high pressures. There’s a whole set of things that nature does incredibly well, and all these techniques that have evolved in nature are in many cases more powerful than things that our industrial approaches have ever been able to match.

Which applications can we expect to see?

Being able to program cells within micro organisms allows us to produce therapeutics and food protein for us to eat, but also the materials that we need in a carbon-neutral, net-zero world. And even the industrial inputs that we might need, for example providing fertilizer for plants without harming the environment.

How does that affect current businesses models?

It really shifts the balance of power, because the companies that can design these organisms are constructing the organisms. The production that takes place is not reusing the old infrastructure that’s been built over 80 or 90 years, and it’s probably not using many of those old those skills. That creates new winners – and in some cases losers in the economy. That’s a destabilizing component to all of this.

Fertilizers, reinvented: Scientists are engineering microbes to grow crops more productively without harming the environment, as BCG and Hellow Tomorrow explain in their report Nature Co-Design (PDF).

The rapid pace of change frightens many people.

I think keeping up is very hard. And I say this as someone who spends his whole time keeping up. But I think what we can do is still to equip ourselves with the understanding of the processes of change, and equip ourselves with where the potential lies.

Why is that so important?

One reason why people feel that this is out of control is because a lot of the dialogue we constructed around technology was that it was something that that other people did to us. Perhaps very, very clever people different to us. And then we will accept – with excitement or with passivity.

You said we need to “lean in”. What if we don’t? If we lean back?

The technologies are going to become more ubiquitous. So you should figure out how you’re going to use them and how you’re going to make them relevant to your context, your community, your town, your industry.

Can we really expect billions of people to become technology experts?

It’s more about developing a wider understanding. Because there needs to be a broader engagement by people in these shifts. One of the things I want to do with the book is explain that this isn’t something to be left just to technologists. This is something that is part of human society, it’s part of human culture. And so it’s really up to us to equip ourselves with sufficient understanding that we can be part of the decision making. Because the alternative choice is that they get imposed on you by large global platform companies, as has been the case for the past 20 years

The Exponential Age

By loading the video you agree to the Privacy Policy of YouTube and accept that your data will be processed by Google.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information