The Impact of Automation: “We Can Help People Adjust”

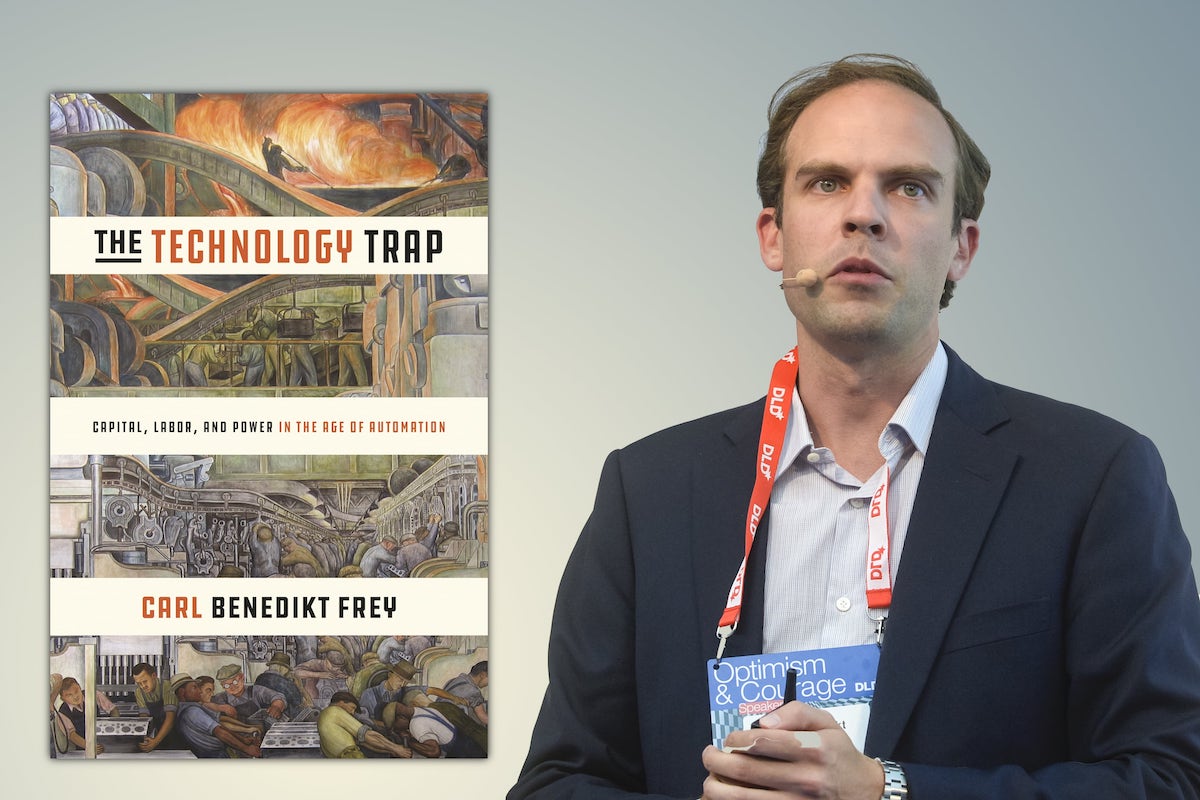

In conversation with DLD, Oxford economist Carl Benedikt Frey speaks about his new book “The Technology Trap” and describes the social impact of automation.

In his new book The Technology Trap, Oxford economist Carl Benedikt Frey examines the parallels between the Industrial Revolution and the digital revolution. Frey, a leading researcher on the future of work, spoke with DLD about the effects of automation on jobs, politics and society. He sees a danger of technology increasing inequality – but there are many ways, Frey argues, to counteract negative consequences of disruption in the short run, so that ultimately a majority of people will benefit, not just a few.

Progress seems to be traveling on board a rocket ship. Technology is advancing faster than ever before, constantly pushing the limits of what’s possible. Successful innovators reap the benefits of a networked, global economy that knows no bounds. At the same time, however, more and more people in Western societies feel that they’re at risk of losing ground.

Carl Benedikt Frey is a Swedish-German economist who directs the program on the Future of Work at the Oxford Martin School in Britain. In 2013, he co-authored a widely cited study which argued that almost half of all jobs in the U.S. could be automated in the foreseeable future.

In The Technology Trap, Frey takes a look at history to get a better idea of what the future might bring. “The spread of every technology is a decision”, he notes and points out that the benefits of technological progress need to be evident to a majority of people to avoid societal unrest. “There is no fundamental reason why technological ingenuity should always be allowed to thrive”, Frey writes, concluding that “technology’s acceptance depends on whether those affected stand to gain from it”.

We spoke with Carl Benedikt Frey at DLD Europe in Brussels where he also gave a speech and participated in a panel discussion. You can watch recordings of both sessions below.

A lot of people fear being replaced by AI and robots. How worried do they really need to be?

It’s important to realize that for society as a whole automation has been a good thing – at least in the long run. It means that we get more productive and companies pay higher wages. It also means that we’re able to produce things that we couldn’t produce otherwise, that there are more goods and services, and overall it means better jobs as well. The automation of mining jobs and manufacturing jobs has meant that people can now work in air-conditioned offices or work in restaurants in much more pleasant and comfortable environments.

But in the short run many people fear for their living.

Yes, on a personal level we have to ask: Is automation a good thing for people that are being replaced by technology, for people who have invested time and money into developing certain skills? These workers may not see much benefit even over the medium term. When people are replaced they lose their livelihoods, the skills in which they invested become redundant. As a result, family incomes are being affected, and the next generation might be affected as well.

How do we manage this disruption?

At this point that’s an open question. When the Industrial Revolution happened we didn’t manage it much at all. People still believed that higher incomes would only translate into larger populations – with no gains on an individual level.

This time around we can actually do a number of things. We can invest more in education and the school system, we can help people to acquire new skills, we can introduce relocation vouchers to make it easier for people with lower incomes to move to better-paid jobs elsewhere.

We can also invest in infrastructure to make housing more affordable where new jobs are being created. And you can do things like decoupling health insurance from having a job. In the U.S. many people are terrified by having their jobs automated away, partly for this reason. If I go to Sweden people are much less concerned.

The Technology Trap: At DLD Europe, Oxford economist Carl Benedikt Frey presented key thoughts from his new book in a keynote speech.

How do you pay for such initiatives?

Income redistribution can be costly, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you can invest in education specifically in communities that are currently lacking support for low-income families. We see that in early-childhood education, for example, the results are overwhelming. The policy essentially pays for itself. Relocation vouchers promise similar benefits in that they enable people to move from non-employment to a place where they actually get a job.

Income inequality is at its highest levels in 50 years, according to the OECD. Should people who reap the benefits of digital change pay higher taxes?

I’m not opposed to taxing people with wealth. But I don’t think it should be a goal in itself. You want to tax wealth to pay for public services which benefit people in the economy as a whole.

Where do you see the biggest difference between the digital and the Industrial Revolution?

In the area of the political economy. A hundred years ago people opposed to automation – the so-called Luddites – got their voice heard but they were unsuccessful because they lacked political clout. Property ownership was still a requirement for voting, which left large shares of the population disenfranchised. Today, the franchise of displaced workers is much greater, so instead of throwing sticks and stones people can make a difference at the election. And if that’s a significant group in the labor market with a collective voice, that becomes more challenging politically, and that is what we’re seeing now.

Is digital change driving polarization and populism?

In essence, the old working class, if you will, have increasingly become politically disenfranchised. They are no longer represented by the mainstream political parties which typically cater to high-income voters on the conservative side of the political spectrum and highly educated, more urban voters on the left. Populists are very effective at tapping into the anger of people who feel that they have no political home any more – and many of them are, shall we say, “value conservative”.

So we’re seeing that it’s very easy to appeal to a group of people who have the feeling that they haven’t benefited from the way the economy has been going for the past 30 years or so. And there’s some truth to that, because as the Western economies have become deindustrialized that has been good for us overall, but it hasn’t been good for this particular group of people.

These processes as such aren’t new. They’re very similar to what we saw during the first Industrial Revolution. But at this time we can actually help people adjust.

You write that many new jobs which are being created a require a much higher level of education. How can somebody who is replaced as a truck driver or bookkeper become a software developer?

I think that’s unlikely to happen. It’s as simple as that. It’s always been the case that people who lost their jobs to automation have traded down for some period of time. But we can use – at least to some extent – the welfare system to compensate people that downgrade into lower-paying jobs.

Wage insurance, for example, is a proposal that is featuring in the American debate. It’s already being implemented with regard to trade, but you can extend it to automation. The idea is that people who shift down from medium-income jobs to low-paying jobs get part of their income topped up by the government and still have decent working conditions compared to what most people had in the past.

For many people, their profession is a large part of their lives and has a big influence on their sense of self. Is it perhaps time that we think differently about work?

Before the Industrial Revolution everybody worked but very few people had jobs in the modern sense. People worked at their home, at their own pace and not at the pace of the clock. And for some people that was a more comfortable, flexible way of life.

You could argue that we’re going back to that now with the gig economy and growing flexibility. This comes at the expense of job security, however. And that goes back to a well-known policy dilemma: The best job for you might be the worst job for me. I think we need to make sure that the labor market offers flexibility for the group that specifically asks for it, and more security for others who are worried about having a regular income.

Automation & AI

By loading the video you agree to the privacy policy of YouTube.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information