The Hidden Link Between Climate Change and National Security

As nature suffers, so do humans. Security researcher Florian Krampe explains why climate action is crucial to preventing conflicts, near and far.

Protecting people starts with protecting the planet. “Climate change is having alarming effects on societies and ecosystems”, the renowned security research institute SIPRI notes in a recent report (PDF) that details how extreme weather, biodiversity loss, heat waves, droughts and flooding impact the health of people, as well as entire communities, around the globe.

Ahead of DLD25 we spoke with Florian Krampe, Director of the think tank’s Climate Change and Risk Programme, about the many ways in which these negative effects can exacerbate poverty, inequality and social unrest – creating risks to national security, the economy, and democracy in often unexpected ways. From January 16-18, 2025, Florian Krampe will highlight more of his findings at DLD Munich.

Florian Krampe

is an acclaimed expert in peace and conflict research and the Director of the Climate Change and Risk Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). His work informs policymakers at numerous international agencies, institutions and governments. (Photo: Elias Hassos/DLD)

Speaker Profile

Why does a peace research institute study biodiversity?

One of the things we have realized is that climate change, environmental degradation and biodiversity loss are changing the security landscape. They also change what peace means in this world.

In that sense it is natural that a peace research institute is starting to focus on these issues. The climate change and risk program that I’m leading is actually one of the largest programs at SIPRI. I think that is representative of the changing security landscape. It is an issue we can’t ignore.

What makes climate change a security risk?

Climate change is a factor that impacts people’s vulnerability, and under certain conditions this is linked to security outcomes. It’s very hard to predict those conditions. In Somalia, it’s community violence. In Mali and parts of South Sudan, it’s farmer conflicts. In South Asia, it’s riots or mass protests. So the same dynamics play out very differently in very different forms of security.

Florian Krampe

SIPRI Institute

“Whether it’s droughts or floods, right-wing populist movements have been able to capitalize on extreme weather.”

Increasingly we see similar effects impacting Europe as well. In Spain, for example, populist movements are able to capitalize on climate impacts – or rather on the failure of a government to respond to the climate impacts. Whether it’s droughts or floods, right-wing populist movements have been able to capitalize on extreme weather.

They use these grievances that exist in society, that are compounded by climate impacts, and capitalize on them. In this context, climate change may not be a national security issue – but it’s certainly a threat to democracy.

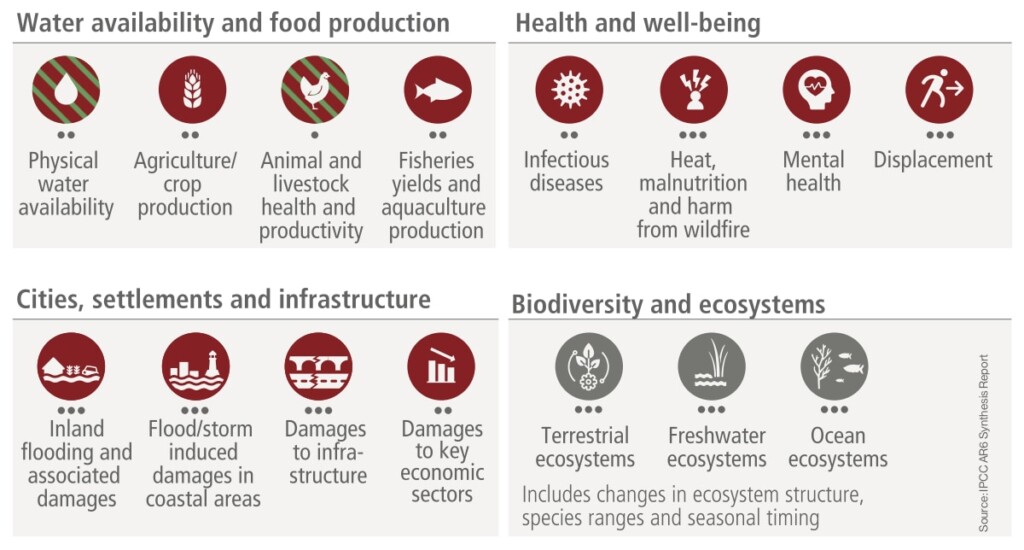

Multiple hazards: Human-caused climate change creates “observed widespread and substantial impacts” to many vital aspects of human existence, according to the IPCC.

Do you see comparable effects in other areas of the world?

Yes, we see a similar dynamic in Somalia and Mali, where extremely violent, extremist groups like Al-Shabaab or the Islamic State of the Sahel are able to capitalize on the grievances and the lack of economic opportunities of people.

Florian Krampe

SIPRI Institute

“When your livelihood is gone you lose part of your identity – this effect is often overlooked and needs more research.”

Importantly, when your livelihood is gone you lose part of your identity – this effect is often overlooked and needs more research, I believe. In some places, militant groups are able to fill the identity void.

People are not necessarily joining these groups because they believe in the same religious cause or because they want to fight for something. They’re joining it to become part of a specific group. It gives them a sense of belonging, and a sense of security as well.

Which grievances tend to become security risks?

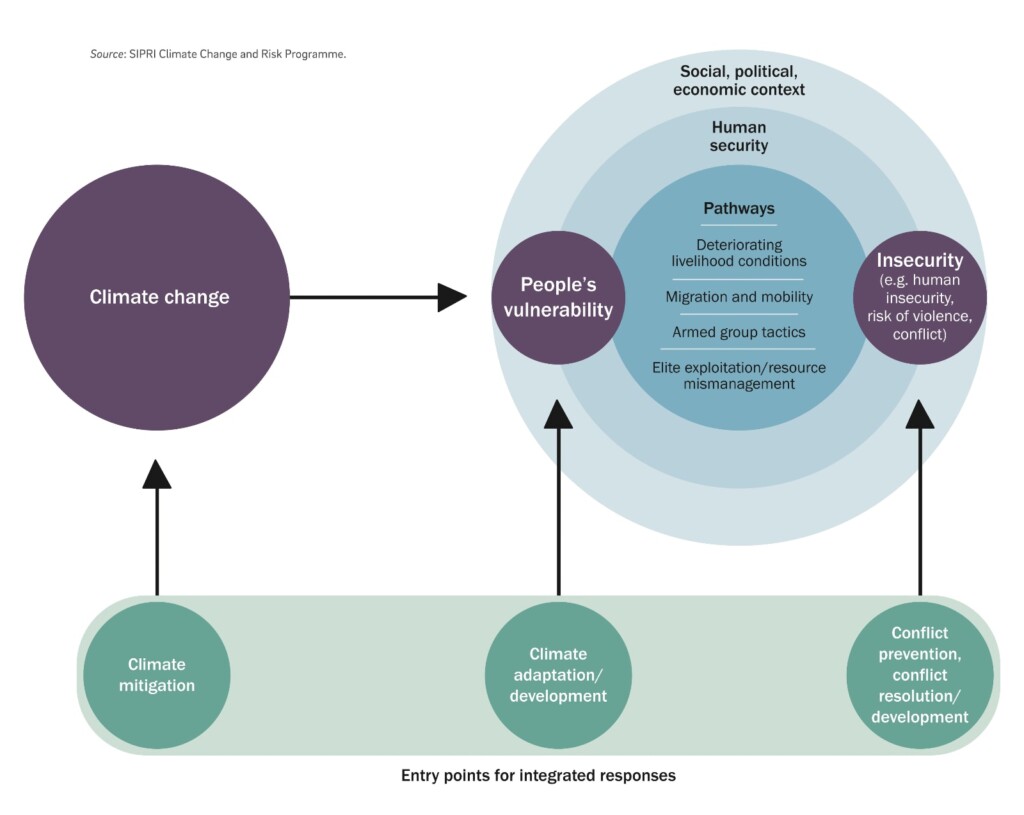

We assess those risks through four pathways: livelihood deterioration; changes in mobility patterns and migration; impact on armed actors; and resource mismanagement.

The first one, livelihood deterioration, is straightforward: You’re losing land, you’re losing your harvests, and you’re facing tremendous challenges. That creates tension between different groups. A lot of the affected groups are already marginalized. So there’s already social friction. But climate change is an additional factor, one more slap that can push people to the brink.

Negative reaction: Climate change increases people’s vulnerability and insecurity, which requires a range of integrated responses, SIPRI research shows.

The same impacts then lead to migration. Desperate people in Somalia move from villages to Mogadishu where they have no opportunities to earn a livelihood. They end up living in impoverished conditions, and if Al-Shabaab comes along and offers 500 euros to join the fight, that is a compelling incentive.

This illustrates that the security implication is not necessarily where the impact is. The location of the climate impact, where the floods hit and displace farmers from their land, is different from Mogadishu or other places that people move to – and that is where tensions start to build up after a while.

That means we see both spatial and temporal factors coming into play, and that is really important to keep in mind.

DLD Munich 2025

For its 20th anniversary, DLD brought together more than 180 speakers from science, business, politics and culture. You can revisit this fantastic event our conference page, which as photos, videos and a list of speakers. To keep in touch and learn about future events, please sign up for our newsletter.

What about the other two factors?

When you look at armed actors, we’re talking about military conflicts. A flood means that you can’t move with heavy military equipment. But there are differences between the armed actors. A big army may find it difficult to operate under extreme weather conditions, while violent groups on motorbikes and very light equipment might still able to navigate the territory. That creates an imbalance, which becomes an advantage for insurgent groups.

The last factor is resource mismanagement. This is the ironic part with climate change, that it brings up all those social and economic issues that we conveniently shoved under the carpet for many decades.

In Mali, for example, we see land tenure rights that didn’t really matter. But all of a sudden, because land resources are shrinking, they become important again. It’s another factor that contributes to grievances and tensions and becomes a security issue because, as a ripple effect, social tensions rise.

Florian Krampe

SIPRI Institute

“We tend to simplify migration, but it’s actually very complicated. Somebody who leaves their home country might have 50 different reasons for doing so.”

How big is the role of climate change in migration?

We tend to simplify migration, but it’s actually very complicated. Somebody who leaves their home country might have 50 different reasons for doing so. We see that when conflicts break out. Some people leave just before violence starts, others wait for months or years.

The important part to keep in mind is that we are usually worried what migration flows will do to us. And I don’t think that’s the biggest issue, really.

Remember that the majority of all of those displaced and migrating stay within the same region, within the affected countries, in different regions, or in neighboring countries.

We are worried about us. But we should be worried about those countries and the pressures that they are facing. And that is why we need to support those countries and build up their resilience against tensions which will inevitably build up.

How can we support these countries effectively?

Sending money would be a start, because one thing we see in the research is: countries that are fragile and conflict-affected get almost no money for climate response. Our climate finance system is so complex that fragile states barely have the ability to fill out the forms. The system is ridiculously complicated.

There’s a multitude of issues on which we do need to invest more money, but we also need to be smart in how we’re spending this money. Maybe a good approach would be to do this not through projects, but through more broader strategic planning, like building it into national adaptation planning.

Florian Krampe

SIPRI Institute

“We’re facing an economic impact which we can’t ignore. Products become more expensive, and consumers are paying for that.”

Some people might say, “We’re talking about countries far away from Europe. Why should we bother?”

Take a case like Yemen and the violent conflict between the government and the Houthi rebels. This has multiple causes, but climate change is certainly a factor. Bring in geopolitics, the war between Israel and Palestine, and all of a sudden Houthis are shooting at ships in the Gulf of Aden.

Those are our economic supply roads, and now container ships have to go around Africa to safely transports goods from Asia to Germany. That means we’re facing an economic impact which we can’t ignore. Products become more expensive, and consumers are paying for that. So whether you like it or not, the issue will come home.

What gives you hope that we will be able to manage these challenges after all?

One aspect is the rapid progress in developing renewable energy. Solar panels in Germany are so cheap today that people who resisted earlier are now saying, “Okay, that works.” Battery technology is quickly improving, too. And I think we see a willingness to increase climate finance in certain regions, especially also in fragile regions, and work more closely together.

Florian Krampe

SIPRI Institute

“I believe we need to take a systems approach, not think in categories like, ‘It’s only a climate adaptation project.’”

We’re also seeing more recognition that it’s often better do multiple things at the same time. Currently, many projects are deliberately kept separate, for example to fight the risks of corruption.

But if I’m building an irrigation channel in Somalia and I’m making that channel climate resilient – that is both climate action and a development program. It helps people who live nearby financially, and it makes their communities more resilient to climate impacts. And if I do that in a certain way, it can also be a peace building effort.

That’s why I believe we need to take a systems approach, not think in categories like, “It’s only a climate adaptation project.” In places like Somalia, how can it ever be one thing only when you’re facing so many challenges at once? And I think we are slowly, but surely seeing actors opening up to this idea.